The largest white diamond to come to market in the U.K. in more than a decade, the VVS1, I-color stone is expected to top $1 million.

Jewelers Uncork New Opportunities

A handful of retailers are lending their talents to the wine and spirits industry. We talked to them about their side businesses for a special feature in our Retailer Hall of Fame issue.

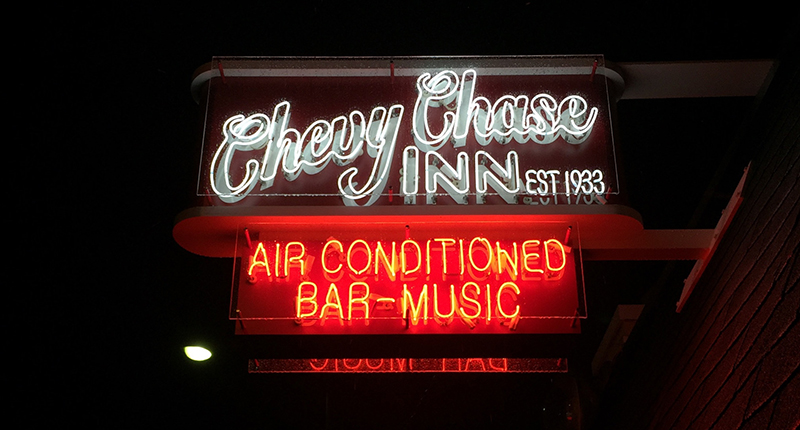

Over the years, the bar solidified its spot as the local watering hole, welcoming generation after generation into its low-key, homestyle atmosphere.

It was even immortalized in a 2013 book titled “Chevy Chase Inn: Tall Tales and Cold Ales From Lexington’s Oldest Bar,” which chronicled its history and shared tales from local patrons.

True to its Kentucky heritage, the inn serves up all types of bourbon, even hosting a “Pappy Thanksgiving” every fall to give customers a chance to try top-shelf Pappy Van Winkle bourbon at cost.

In 2015, Bill Farmer, owner of Farmer’s Jewelry, and two of his friends, bought the 85-year-old bar, saving it from turning into a run-of-the-mill retail space.

Like the Chevy Chase Inn, Farmer’s Jewelry has been stitched into Lexington’s neighborhood fabric since 1950, when his father opened the store on the same block of Euclid Avenue as the inn and a row of retail shops, including the city’s oldest flower shop.

“We approached buying Chevy Chase Inn as a chance to save something,” says Farmer, who felt the destruction of the bar would “ruin a lot of memories for a lot of people.”

The jeweler, who also serves as a Lexington-Fayette Urban County Council member, was already wearing many hats before deciding to move into the bar business.

“Retail drives you to drink,” says Farmer, with a hearty laugh.

In all seriousness, though, he notes that both his jewelry business and his bar business have something in common—they are there for people to celebrate and commemorate happy occasions.

Lessons learned as a jeweler carry over to his bar business, says Farmer, particularly the art of listening.

“If you can listen in retail, you can learn what the customer wants. Same in the bar.”

For jewelers looking to branch out into other areas, Farmer advises looking for an opportunity (like he had) within an existing local business or interest and being ready when that opportunity presents itself.

He warns against stretching oneself too thin or jumping too hastily into the unknown.

In the Heart of California Wine Country

For California jewelers Steve and Judy Padis, opportunity presented itself in 2004. They purchased property in the Oak Knoll region of California, which is located about an hour north of San Francisco in Napa County, and slowly began building out Padis Vineyards over 15 acres.

The couple owns and operates a handful of Padis Jewelry locations around the San Francisco Bay area but also are longtime wine collectors, amassing a stash of more than 10,000 bottles.

It was Judy who introduced her husband to the world of wine during the couple’s dates in Napa Valley.

“I had never really experienced wine tasting,” Steve admits. “It became a passion and as soon as we could afford it, we decided we were going to make our own wines.”

The Padises had their first vintage in 2008 with the help of master winemaker Robert Foley.

“If someone asks me what I do I say, ‘I do diamonds and wine.’” — Steve Padis, Padis Jewelry and Padis Vineyards

Currently, Padis Vineyards produces around 3,000 cases of wine per year, mostly red wine from their homegrown red grapes. About 10 percent of their production is chardonnay, which is made from grapes they’ve purchased.

Their inner jeweler shines through on their wine labels, with a cabernet dubbed “Brilliance” and a blend of cabernet sauvignon and syrah called “Sintilation.” (And, no, that is not a typo.)

“If someone asks me what I do I say, ‘I do diamonds and wine,’” Steve says.

The vineyard is situated between Napa’s warm upper valley and the cooler Los Carneros region to the south, just about an hour away from the couple’s San Francisco stores.

The seasonality of the wine business works in the Padises’ favor, slowing down as the jewelry business revs up in November and December.

The two worlds meet often, says Steve, with a lot of jewelry customers visiting the winery and vice versa. The couple has even held master classes at the winery, giving people a view of picturesque Napa Valley while they examine another natural beauty—the diamond.

European Winemaking in Western Pennsylvania

For jeweler Tom Glatz, the opportunity to branch out into the alcohol business came knocking at the back door.

The tasting room for Glatz Wine Cellars operates out of the rear of Glatz Jewelers in Aliquippa, Pennsylvania, a small town about 25 miles northwest of Pittsburgh.

Though the winery began in 2000, Glatz’s roots in winemaking go way back.

“People ask me how long I’ve been making wine. Longer than jewelry, I tell them,” he says, noting that his family has been making wine in Europe, mainly in Germany and France, for more than 200 years.

It’s still a family affair for Glatz, who operates the winery and jewelry store—which opened in 1976—with his wife Marlene, and his sons, Aaron (who makes the wine), and Dale (who repairs the jewelry).

The vineyard is just a few miles away from the store, spanning six acres on the family’s farm in neighboring Hopewell Township.

As with the Padises, the jeweler’s touch is apparent upon reading the wine list at Glatz, with bottles bearing names such as “Amethyst,” “Tanzanite,” “Topaz” and “Chocolate Diamond.”

The store and the winery flow seamlessly into each other. Customers often grab a glass to sample from the winery in the back, then step out onto the patio (located off the side of the store) to inspect potential jewelry purchases in the natural light.

The winery also doubles as an event space for local charities and fundraisers, which, in turn, helps to bring more attention to the jewelry business.

From Silicon to Napa Valley

While jewelers-turned-vintners have uncorked an additional revenue stream that pairs nicely with their stores, a small-production winery comes with its own challenges, says Carole Lawson, CEO of the Salem, Oregon-based Craft Wine Association.

Some of these challenges are unique to wine-making, while others will sound familiar to retailers, including: How do I entice people to buy what I’m selling?

There are tools and algorithms available to get a ballpark figure on what it costs to open a winery, but Lawson suggests adding 20 to 30 percent on top of that, accounting for weather and operating requirements that can vary by state.

“There’s a fantasy about what it’s like [to own a vineyard.] You don’t think about the pruning, the planting, the pests and the weather that can impact the production of the grapes themselves.” — Carole Lawson, Craft Wine Association

Glatz estimates he sank about $250,000 into producing his first bottle.

And, although the family has been making wine since 1980, it took the Glatzes years before they were able to sell their first bottle, due in part to Pennsylvania’s particularly strict alcohol laws.

After an arduous licensing process, including several attempts at getting their bottle labels approved, the Glatzes began marketing their wine in 2007.

Glatz once thought he would retire to his winery—a relaxing respite after years in the stressful world of retail—but has since thought better of it after learning first-hand what goes into the day-to-day operations of a vineyard.

“It’s a lot of work, about 14 hours a day,” says Glatz, who relies on his son and master winemaker Aaron and employees to do the manual labor.

“There’s a fantasy about what it’s like,” says the Craft Wine Association’s Lawson. “You don’t think about the pruning, the planting, the pests and the weather that can impact the production of the grapes themselves.”

The biggest challenge to operating a winery, she says, is being realistic.

One can buy a vineyard or buy grapes, press them, and bottle the wine with beautiful labels, but the real challenge is marketing it and getting people to buy it.

Still, Lawson, who spent decades working in Silicon Valley before “flunking out of retirement” and starting the Craft Wine Association, understands what draws people from other industries to wine.

“There is a romance about the wine industry,” she says, noting its similarity to jewelry in this way. “The marketers have done a great job of making it feel opulent and [giving it] a sense of having arrived.”

The Latest

Skelly shares her plans for reimagining the fine jewelry retailer she re-acquired after it faltered last year.

The collection takes inspiration from the emotional space between people, moments, and experiences.

Every jeweler faces the same challenge: helping customers protect what they love. Here’s the solution designed for today’s jewelry business.

The jewelry giant released preliminary results for the fourth quarter and full year on Monday, with final results slated to come next week.

The retailer also gave an update on its vendor partnerships.

The award-winning actress is the “epitome of modern allure,” the brand said.

With refreshed branding, a new website, updated courses, and a pathway for growth, DCA is dedicated to supporting retail staff development.

The “Bloom” collection draws from the flower power movement of the 1960s and ‘70s with inlay pendants offered in eight colorways.

The unique piece was one of the custom works offered at the foundation's recent silent art auction, which garnered nearly $15,000 in total.

Bulgari named Gyllenhaal as its brand ambassador for his embodiment of artistic depth, intellectual curiosity, and warmth.

Awards were given to four students, one apprentice, and an emerging jeweler.

The top jewelry lot of the late model’s estate sale, hosted by John Moran Auctioneers, was an Oscar Heyman & Brothers for Cartier necklace.

Moses, who started at GIA’s Santa Monica lab in 1976, will leave the Gemological Institute of America in May.

Increased competition, falling lab-grown diamond and moissanite prices, and the rising cost of gold took a toll on the moissanite maker.

The earrings, our Piece of the Week, feature pink tourmalines as planets orbiting around an aquamarine center set in 18-karat rose gold.

“The Price of Freedom” campaign video for International Women’s Day confronts the quiet violence of financial control.

Also, a federal judge has ordered that companies that paid tariffs implemented under the IEEPA are entitled to refunds.

The ever-growing collection, which just expanded with the addition of Olga of Kyiv, features cameos of 12 women from history.

We asked a jewelry historian, designer, bridal director, and wedding expert what’s trending in engagement rings. Here’s what they said.

The annual event will be held in Orlando, Florida, from Sept. 14-17.

The “Outlander” star modeled for the digital cover of the magazine’s spring issue, which features a story on her relationship with jewelry.

This year’s annual congress, which will mark the confederation’s 100th anniversary, will take place this fall in Italy.

Beverly Hills was chosen as the location for the brand’s first store, designed as a “private residence for modern monarchs.”

Kering, Apple, and other retailers have reportedly temporarily closed stores in the Middle East region in light of the recent conflicts.

Beth Gerstein discusses the vibe of the new store, what customers want when fine jewelry shopping today, and the details of “Date Night.”

Nearly half of buyers are prioritizing silver and fashion collections this season, organizers said.