Out & About: Watching De Beers Grow Diamonds in Oregon

Editor-in-Chief Michelle Graff shares her opinions on the state of the lab-grown diamond market following a trip to the Lightbox factory.

Some 14 years later, I received another invitation to take a trip with De Beers, this time to observe a different kind of operation—the factory where it grows diamonds outside Portland, Oregon.

I find the science behind growing diamonds much more interesting than all the tedious back-and-forth about lab-grown vs. natural (and I’m forbidden from having that debate anyway, per National Jeweler’s Lenore Fedow).

I think both have, and will continue to have, their place in the industry; what exactly that place will be—the stone of choice for engagement rings, the main driver of fashion jewelry, or some mix thereof—remains to be seen, particularly in this unpredictable climate.

On a personal note, I prefer natural diamonds to lab-grown, particularly for big milestone gifts to myself, though I can see the appeal of lab-grown diamond jewelry for more “fun” pieces, particularly those set with a pink or blue diamond, which are largely unattainable due to their cost.

But those pinks and blues are only part of the production run at the Lightbox, which I visited in early November with a group of journalists on a tour led by the site’s general manager, Adam O’Grady.

Stepping Inside

Lightbox is in Gresham, Oregon, about 25 minutes east of Portland.

De Beers chose Portland because it needed to build the factory somewhere that has a reasonable cost-per-kilowatt for energy, has access to renewable sources of energy, and doesn’t get too hot in the summer.

Portland checks all three boxes, though it’s worth pointing out that the extreme weather patterns brought about by climate change are a concern to Lightbox just as they are a concern to the diamond miners that rely on ice roads. Portland, where it normally doesn’t get much hotter than 75-80° F, saw temps soar past 100° F this past summer.

The Lightbox factory employs about 80 people, 45 of whom are employed in direct production. It’s staffed 24/7 and its reactors run around-the-clock as well.

Mounted at the front entrance to the factory is a massive screen monitoring each reactor. Someone on the tour compared it to the control room on the Starship Enterprise, but as a Star Wars fan I didn’t get the reference.

The screen shows you which reactors in the factory are actively growing diamonds and which are down due to mechanical issues or scheduled maintenance.

For those that are active, the screen shows what they are growing—meaning size and color of diamond—and how much longer they have to cook, so to speak, before the diamonds are done.

How They Grow

The Lightbox factory uses chemical-vapor deposition (CVD) technology to grow diamonds.

CVD is a newer, and more expensive process than the high-pressure, high-temperature (HPHT) method mostly used to grow industrial-grade diamonds.

CVD involves growing substances atom-by-atom on a substrate material. In the case of Lightbox, that substrate material is diamond.

O’Grady told us that De Beers manufactures the substrate it uses for Lightbox diamonds on site, setting aside a small amount of production each day for future diamonds.

The diamond substrate plates are placed on a carrier by a robot, which is quicker and saves the factory’s employees from a tedious task, before they are delivered to their designated reactors.

To transform the plates, which to me look like gray Listerine strips, into actual stones, gases are pumped into each reactor and the machine is heated up to 6,000° C (10,832° F). The mix of gases depends on what the machine is growing: white, pink or blue diamonds.

O’Grady said it takes “a couple hundred hours to grow a couple of hundred stones” and, generally speaking, the bigger the stone needs to be, the longer it has to cook.

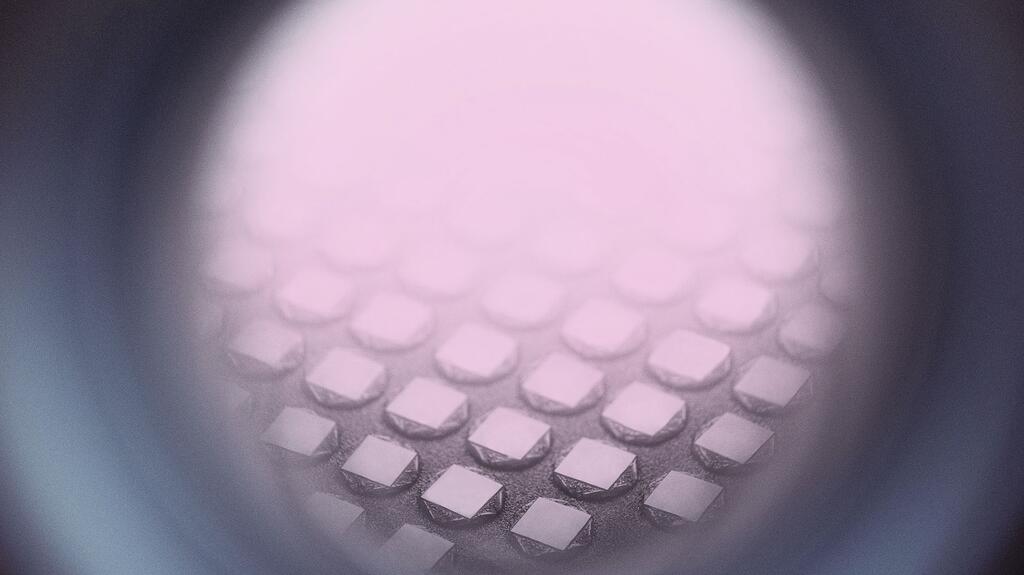

Each reactor is equipped with a peephole of sorts that you can look through to see the diamonds as they grow.

These are less necessary than they used to be since each machine is computer-monitored, O’Grady told me, but “people still like looking in them.” (It’s a bit like peeking in the oven to check on your cinnamon rolls; I understand the appeal.)

So, someone asked O’Grady, is the Lightbox factory the most high-tech diamond-growing facility in the world? “I think it’s safe to assume we are at the top end of that table,” he said.

After Growth

Once the diamonds are done, some initial cutting and polishing is done on-site, though the stones are not fully finished there. They are shipped to a cutting and polishing factory in India before being set into jewelry.

The pink and blue stones are HPHT treated post-growth to improve their color saturation and consistency, while all 2-carat and stones for “Finest,” its new premium line, are also HPHT treated to improve their color to D, E or F and their clarity to VVS. De Beers has just begun disclosing these treatments to consumers.

As you might remember, when De Beers launched Lightbox to much uproar at the Vegas shows in 2018, it introduced a strict pricing structure, $800/carat, and said it was marketing it as a “fun” product for somewhat-less-special special occasions, like a Sweet 16, positioning natural diamonds as the stone of choice for more substantial milestones.

In the years since, that uproar has calmed down as the lab-grown diamond market has evolved and the brand has evolved too, expanding beyond its originally declared mission, growing bigger, better diamonds.

The 2-carat diamonds I peeped growing in Portland are a new addition for Lightbox, as is the sale of loose diamonds, and “Finest,” the aformentioned premium line of D-to-F color, VVS diamonds it launched in August. “Finest” diamonds are priced at $1,500/carat.

I am curious to see where Lightbox, and the lab-grown market, will go from here.

In a forecast published this fall, diamond industry analyst Paul Zimnisky wrote that in the long term, growth in the sector will come mainly in fashion jewelry and industrial diamonds, a forecast I initially agreed with but then began to waver on following some recent headlines.

Signet Jewelers announced during its Q3 earnings call earlier this month that it is expanding its selection of lab-grown diamonds in some of its bestselling bridal lines.

The Knot’s latest survey showed that people’s stances on lab-grown stones—not just diamonds but moissanite as well—are softening when it comes to engagement rings.

And, as I noted above, De Beers is growing bigger, better diamonds and now also selling loose Lightbox stones, which seem destined for engagement rings.

While none of this is hard proof of where the market is definitively headed, what is certain is that years from now, people will find it hard to believe there was ever so much debate about lab-grown diamonds.

They’ll be like Prohibition (seems so strange now to think alcohol was once illegal, right?) or cannabis, which in my relatively short lifetime, has gone from being illegal everywhere to being legal in some form in all but 12 states.

People’s perspectives on what’s good or bad, what’s acceptable or unacceptable, are always changing. What’s hotly debated among members of one generation often isn’t even a point of conversation with the next.

The Latest

Guthrie, the mother of “Today” show host Savannah Guthrie, was abducted just as the Tucson gem shows were starting.

Butterfield Jewelers in Albuquerque, New Mexico, is preparing to close as members of the Butterfield family head into retirement.

Paul Morelli’s “Rosebud” necklace, our Piece of the Week, uses 18-karat rose, green, and white gold to turn the symbol of love into jewelry.

Launched in 2023, the program will help the passing of knowledge between generations and alleviate the shortage of bench jewelers.

The nonprofit has welcomed four new grantees for 2026.

Parent company Saks Global is also closing nearly all Saks Off 5th locations, a Neiman Marcus store, and 14 personal styling suites.

It is believed the 24-karat heart-shaped enameled pendant was made for an event marking the betrothal of Princess Mary in 1518.

Criminals are using cell jammers to disable alarms, but new technology like JamAlert™ can stop them.

The AGTA Spectrum and Cutting Edge “Buyer’s Choice” award winners were announced at the Spectrum Awards Gala last week.

The “Kering Generation Award x Jewelry” returns for its second year with “Second Chance, First Choice” as its theme.

Sourced by For Future Reference Vintage, the yellow gold ring has a round center stone surrounded by step-cut sapphires.

The clothing and accessories chain announced last month it would be closing all of its stores.

The “Zales x Sweethearts” collection features three mystery heart charms engraved with classic sayings seen on the Valentine’s Day candies.

The event will include panel discussions, hands-on demonstrations of new digital manufacturing tools, and a jewelry design contest.

Registration is now open for The Jewelry Symposium, set to take place in Detroit from May 16-19.

Namibia has formally signed the Luanda Accord, while two key industry organizations pledged to join the Natural Diamond Council.

Lady Gaga, Cardi B, and Karol G also went with diamond jewelry for Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime show honoring Puerto Rico.

Jewelry is expected to be the No. 1 gift this year in terms of dollars spent.

As star brand Gucci continues to struggle, the luxury titan plans to announce a new roadmap to return to growth.

The new category asks entrants for “exceptional” interpretations of the supplier’s 2026 color of the year, which is “Signature Red.”

The White House issued an official statement on the deal, which will eliminate tariffs on loose natural diamonds and gemstones from India.

Entries for the jewelry design competition will be accepted through March 20.

The Ohio jeweler’s new layout features a curated collection of brand boutiques to promote storytelling and host in-store events.

From heart motifs to pink pearls, Valentine’s Day is filled with jewelry imbued with love.

Prosecutors say the man attended arts and craft fairs claiming he was a third-generation jeweler who was a member of the Pueblo tribe.

New CEO Berta de Pablos-Barbier shared her priorities for the Danish jewelry company this year as part of its fourth-quarter results.

Our Piece of the Week picks are these bespoke rings the “Wuthering Heights” stars have been spotted wearing during the film’s press tour.