Bulgari named Gyllenhaal as its brand ambassador for his embodiment of artistic depth, intellectual curiosity, and warmth.

Field Gemology & Geographic Origin: 5 Questions Answered

GIA’s Aaron Palke discussed expeditions, origin determination and the future of field gemology in a recent webinar.

The conversation is so dominant, in fact, that the GIA’s scientific journal, Gems & Gemology, dedicated its entire Winter 2019 issue to the topic.

On April 23, Aaron Palke, senior manager of research at GIA, hosted a webinar as part of the lab’s recently launched “Knowledge Sessions” to talk about the GIA’s field gemology program and the role it plays in geographic origin determination.

I covered the topic of including gemstone origin on reports in my in-depth story for our 2018 State of the Majors issue.

The topic of field gemology continues to intrigue me, and I want to keep up with the origin conversation, so I tuned in to hear what Palke had to say.

Here are five notable topics he covered that trade members might find interesting. To watch the full session, visit the GIA’s YouTube channel.

Why is origin important?

A colored gemstone’s geographic origin is closely aligned with the conversation about its perceived value, Palke said.

Color, transparency and size are some of the most obvious and important value characteristics, but so too is a stone’s “story.”

He used the example of a customer buying a ruby.

Would they rather buy a natural ruby, and tell the story of a miner and how he or she retrieved the stone, or would they rather buy a lab-grown and tell the story of stone created by man?

There’s nothing wrong with either, but the market will “attach a different value” to the lab-grown stone based on that story, Palke said.

One can think about geographic origin in much the same way, he added; it’s part of a stone’s story.

If a client wants a natural ruby, do they then want one from Mozambique, which produces a lot of high-quality stones but is a modern source, or do they want one from Mogok in Myanmar, which is an ancient source? The market will give the Burmese stone a different value because of this story.

What role does field gemology play in origin determination?

GIA started offering origin determination services on lab reports in 2006 because of market demand and ramped up its research so it could offer the service more accurately for clients.

This came with the realization, Palke said, that for accurate determination, the lab had to build a reliable reference database.

So, in 2008, GIA created a field gemology department to build this database, a collection of gem materials with known provenance against which researchers could compare a client’s stone.

Since its establishment, the department has gone on 95 expeditions to 21 countries on six continents, Palke said, noting they’ve traveled most frequently to East Africa and Southeast Asia.

During these expeditions, the field gemologists’ goal is to collect stones as close to the source as possible and gather as much information as they can regarding where the stone came from, how it was collected and from whom.

Since the team can’t always get the gem materials straight from the source, they classify the samples based on how they were collected.

A-type, for example, is mined directly by the field gemologist, while B-type stones were collected at the mine, with the field gemologist witnessing the mining but not removing the stones from the ground themselves.

RELATED CONTENT: What It’s Like to Be a Field Gemologist, Part 1 and Part 2

The system ends at F-type, which are samples collected on the international market.

When the samples are brought back to the lab, researchers do “everything from the low tech to the high tech,” according to Palke, from microscopy to look at inclusions to various spectroscopy techniques.

The information they get is added to a database accessible by gemologists at GIA’s five identification labs.

The reference collection itself now includes more than 22,000 samples that weigh a total of more than 1 million carats.

What challenges does today’s market bring, and how is research addressing them?

Many new sources and mines have popped up in the past few decades.

One of the biggest developments in the colored stone mining sector in the 20th century has been the rise of East Africa, offering colored gemstones of all kinds from Kenya to Madagascar.

“All of a sudden, we have a lot more options that you have to consider to determine where a stone came from,” Palke said.

The state-of-the-art technology now available can help labs narrow down origin possibilities by providing multiple data sets with which to work and compare.

One of those methods GIA uses is a technique called laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry, or LA-ICP-MS, which measures trace elements in stones with a superior level of precision and accuracy.

GIA researchers can compare those measurements with data from the reference collection to help narrow down an origin possibility.

But what the data shows—and what is often cited as an issue among those concerned with the reliability of origin determination services—is that with the rise of all these new deposits, there tends to be overlap in physical properties between stones from different areas.

GIA has developed other resources to help make origin calls more accurately, like the use of statistical tools that offer a better way to crunch the data from trace element analysis.

Selective plotting based on k-nearest neighbors, for example, is a method based on the idea of predicting unknown values by matching them to the most similar known values, according to DataQuest. For researchers comparing trace element chemistry, it helps them look at the data from more dimensions.

Still, GIA and other labs continue to emphasize that geographic origin determinations on reports are opinions, not indisputable facts.

Where have GIA’s field gemology expeditions gone recently?

An important development over the last several years has been the rise of Ethiopia in the gem world—blue sapphires at Axum and emeralds in Shakiso joined opal offerings from the country.

Because the material hit the market so quickly and made waves, Palke said they knew they had to send a team there. In early 2018, they went to collect emeralds, opals and sapphires from Ethiopia.

In 2018, the GIA field gemology team went to Sri Lanka to look into blue sapphires. That same year, as well as in 2019, they went to Mogok, Myanmar for sapphires and a variety of other materials.

Early last year, they traveled to the Malysheva emerald mine in the Russian Ural Mountains.

What they found there was a large, sophisticated operation producing a lot of emeralds.

“There’s every reason to believe these stones are going to be coming through the lab,” Palke said.

They also collected samples from demantoid garnet mines in the same region. Though GIA doesn’t offer origin determination for demantoid yet, Palke said the lab is “actively looking into it.”

There are a few other benefits to the field gemology expeditions Palke mentioned, one being they act as “fact-finding missions” so GIA gains insights into who’s mining in an area, how much is being produced, the quality of the stones, and how they’re reaching the market.

Additionally, the samples collected can also benefit other research areas. The demantoid garnet samples, for example, will help in heat treatment identification.

What’s the future of origin determination?

The value the market places on origin won’t go away any time soon, and it’s not likely origin determination services will either, Palke said.

As such, GIA is looking into expanding its origin determination services for additional materials.

In 2019, the lab rolled out origin reports for alexandrite after years of research and sample collecting.

Palke said that service has seen “pretty good success” so far.

It is also looking into demantoid garnet, as mentioned before, opal, and potentially others, but the future of the area will also depend on advances in technology.

And because of the growing interest in a transparent supply chain from mine to consumer, GIA is developing a new service called the Colored Stone Origin and Traceability Report, not entirely unlike the one it rolled out for diamonds last year.

It would involve a client submitting a rough stone with accompanying documentation about where, when and from whom it was purchased.

The lab would examine the stone, document its physical properties and return it to the client, who would then cut and resubmit the gemstone.

GIA would study it again and, if the physical properties of the cut stone match the rough characteristics, it would issue an origin report including a photo of the rough and faceted gemstone and a statement that it was accompanied by documents indicating where it was purchased.

“Essentially, the idea is to get the gemological laboratory more involved in more parts of the supply chain for colored stones in order to help get some more confidence in the trade for this sustainability aspect,” Palke said.

The Latest

Awards were given to four students, one apprentice, and an emerging jeweler.

The top jewelry lot of the late model’s estate sale, hosted by John Moran Auctioneers, was an Oscar Heyman & Brothers for Cartier necklace.

Every jeweler faces the same challenge: helping customers protect what they love. Here’s the solution designed for today’s jewelry business.

Moses, who started at GIA’s Santa Monica lab in 1976, will leave the Gemological Institute of America in May.

Increased competition, falling lab-grown diamond and moissanite prices, and the rising cost of gold took a toll on the moissanite maker.

The earrings, our Piece of the Week, feature pink tourmalines as planets orbiting around an aquamarine center set in 18-karat rose gold.

With refreshed branding, a new website, updated courses, and a pathway for growth, DCA is dedicated to supporting retail staff development.

“The Price of Freedom” campaign video for International Women’s Day confronts the quiet violence of financial control.

Also, a federal judge has ordered that companies that paid tariffs implemented under the IEEPA are entitled to refunds.

The ever-growing collection, which just expanded with the addition of Olga of Kyiv, features cameos of 12 women from history.

We asked a jewelry historian, designer, bridal director, and wedding expert what’s trending in engagement rings. Here’s what they said.

The annual event will be held in Orlando, Florida, from Sept. 14-17.

The “Outlander” star modeled for the digital cover of the magazine’s spring issue, which features a story on her relationship with jewelry.

This year’s annual congress, which will mark the confederation’s 100th anniversary, will take place this fall in Italy.

Beverly Hills was chosen as the location for the brand’s first store, designed as a “private residence for modern monarchs.”

Kering, Apple, and other retailers have reportedly temporarily closed stores in the Middle East region in light of the recent conflicts.

Nearly half of buyers are prioritizing silver and fashion collections this season, organizers said.

The “Live Now. Polish Later.” campaign features equestrians wearing the brand’s jewels while galloping across the icy plains of Kazakhstan.

The precious metals provider has promoted Jennifer Ashworth to the role.

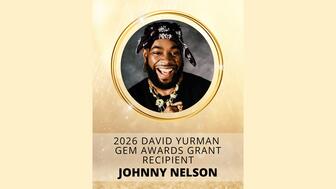

Nelson will be honored as the inaugural grant winner at the Gem Awards gala on March 13.

Experts from India weigh in the politics, policies, and market dynamics for diamantaires to monitor in 2026 and beyond.

The American precious metals refiner’s day-to-day operations remain the same post-acquisition.

These aquamarine jewels channel the calming energy of the March birthstone.

The “Innovative Design” category and award will debut in the Spectrum division of this year’s AGTA Spectrum & Cutting Edge Awards.

Consumers were somewhat less worried about the future, though concerns about rising prices and politics remained.

Foerster is this year’s Stanley Schechter Award recipient.