State of Colored Stones: The Big Three in the Modern World

Sapphires, emeralds, and rubies are finding their place in a U.S. market captivated by the gemstones once referred to as “semi-precious.”

Sapphires, emeralds, and rubies, the Big Three of the colored gemstone world, have long been revered for their beauty and rarity, coveted for centuries by consumers worldwide.

It wasn’t long ago that the designation of “precious” was reserved for only these three gemstones and diamonds, with everything else deemed to be “semi-precious.”

With a long history of association with royals, the terms Burmese ruby, Colombian emerald, and Kashmir sapphire are familiar references to the most valuable gemstones to exist, and many gem dealers still argue it’s simply just the truth.

The landscape around trading the Big Three is evolving, however, as mining technology advances, sources dry up (and new ones are discovered), tastes change, and the industry navigates complex global politics.

The U.S. market, driven in part by higher prices post-COVID and the lack of super-fine material available, has seen dealers recently adjust what they define, and can market, as valuable.

However, the finest untreated sapphires, rubies, and emeralds still command the highest prices of any gemstone, and the appetite for the best and the rarest remains strong.

A Matter of Price

A simple understanding of the law of supply and demand can explain why prices of the Big Three, in the finest quality, are skyrocketing, but there is some nuance.

Gemstone dealer and bespoke jeweler Simon Dussart of Asia Lounges explains, “There used to be three prongs in the market—the low, the mid-range, and the high range. One could argue there was a fourth one, the super high end, but that’s like, an oddity of the high end.

“But the mid-range is dying.”

The loss of interest in this category, which he describes as eye-clean material, the bread-and-butter for the average self-purchaser, is affecting the mining business, Dussart says.

“A lot of the mines are no longer profitable. They needed to have all three segments in order to produce, and now they are stuck producing for the low end, which demands increasingly lower prices, but they can’t really do it [that way], so you’ve got more and more treated materials.

“The trade has an increased demand for higher-quality material that is untreated, which is one of the reasons—but not the only reason—why the price of the material is skyrocketing.”

Since the pandemic, untreated fine sapphires have tripled in price, and Dussart says ruby was inaccessible for him even before the pandemic.

“I seldom go anywhere above 3 carats in the red and blue department,” he says. “Rubies, pre-COVID, that was out of my range anyway because it was already in the six figures, but now it’s like, forget about it. It’s impossible.”

Red-Hot Ruby

Today, untreated fine-quality ruby is exceedingly rare, making it basically a specialized market.

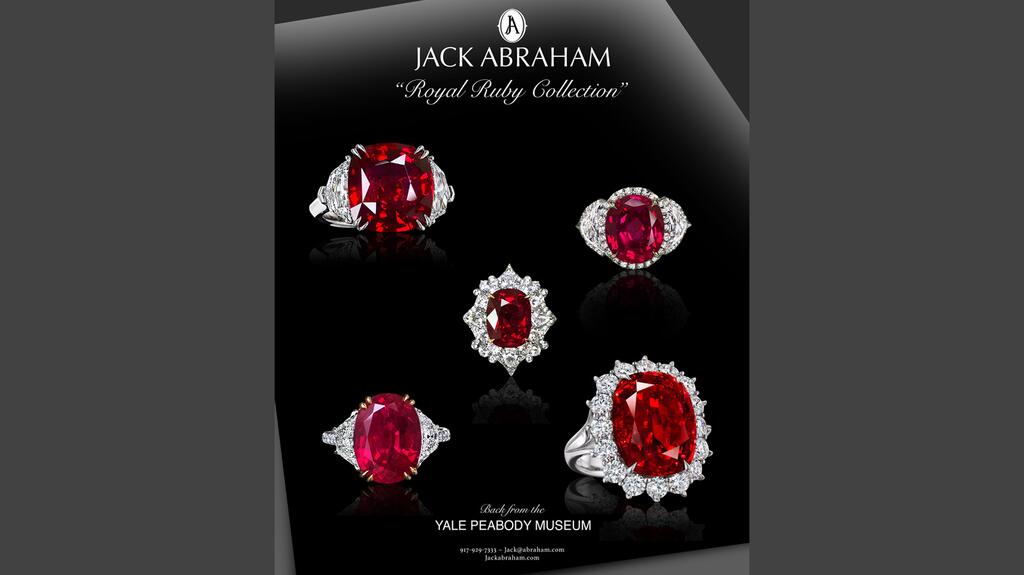

A museum-worthy set of rubies ranging in weight from 7.11-17.88 carats sourced from five different countries—Myanmar, Tajikistan, Thailand, Mozambique, and Madagascar—took longtime collector Jack Abraham more than 40 years to curate, he said in an interview with the American Gem Trade Association’s Prism magazine.

To many in the trade, material from Myanmar’s (formerly Burma) Mogok Valley remains incomparable in quality, but production has decreased significantly.

Earlier this year, Gemfields published “Understanding the Global Supply of Emerald, Ruby and Sapphire.”

The research reviews the evolution of colored gemstone supply over the past 40 years. It’s also an update to the mining company’s 2022 global market analysis of the Big Three.

The report stated that, as of 2009, more than 90 percent of the rubies with a price above $50,000 per carat auctioned at Christie’s were from Mogok, a testament to the material’s popularity and value.

According to Gemfields’ report, the drop in production can be explained by the depletion of the deposits—the Mogok Valley mines as well as the deposit discovered in 1992 in nearby Mong Hsu—but also the increase in privately owned mines, which aren’t obligated to report production.

The main source of ruby production today comes from deposits in northeast Mozambique, which were discovered in the late 2000s.

Although Gemfields announced a record per-carat price ($321.94) from its December 2024 auction of mixed-quality rough rubies from its Montepuez mine, those who have been attending rough sales in the region report that, generally, the quality and quantity of the material are decreasing.

However, the mine remains the sole option for bigger brands that require coherence in material, such as precisely calibrated melee-size ruby with consistent color.

Rubies are also mined, on a much smaller scale, in pockets across several other countries, such as Vietnam, Tanzania, and Sri Lanka, as well as Afghanistan, though trading involving the latter poses some challenges for U.S. dealers.

Last year in Afghanistan, the Taliban, which took control of the country in 2021, indicated it was going to focus on minerals to help Afghanistan’s economy.

In 2022, the U.S. government issued a license allowing for economic activity in Afghanistan, as long as it was not linked to the Taliban or any persons or entities on the Office of Foreign Assets Control’s sanctions list.

So, if a dealer or a company is not connected to the Taliban and not sanctioned, they could trade legally, though it is not likely, according to the Jewelers Vigilance Committee, because it would be very difficult to prove a business is unlinked to the Taliban, as the entity is the government of Afghanistan.

However, during a presentation on the colored gemstone market in Tucson, GemGuide Editor-in-Chief Brecken Branstrator said one of her sources confirmed that rough gemstones are still flowing out of Afghanistan, largely through Pakistan.

International and at-source politics are an unavoidable aspect of dealing in gemstones, from years-long U.S.-imposed sanctions banning Burmese rubies to current-day criticisms of the mining concession in Mozambique as Gemfields navigates heightened illegal activity amid the country’s civil unrest.

Still, there are vendors committed to ethical practices, a surging area of interest within the industry, that are leaning into alternative ruby sources.

A few years ago, wholesaler Columbia Gem House launched its “Pomme Ruby,” collection, featuring “apple red” gemstones produced by artisanal miners in Madagascar.

“For sourcing-conscious designers, Pomme Ruby is the dream gemstone. Its untreated nature and traceable supply chain make it a standout choice for those seeking luxury with responsibility,” says Natasha Braunwart, the company’s brand and corporate social responsibility manager.

At the Ethical Gem Fair in Tucson this year, Virtu Gems debuted rubies mined and cut in Kenya.

While the quality of rubies from these alternative regions tends to be lower, options like these can offer interesting, non-traditional ruby color and peace of mind regarding responsible sourcing.

The Other Corundum

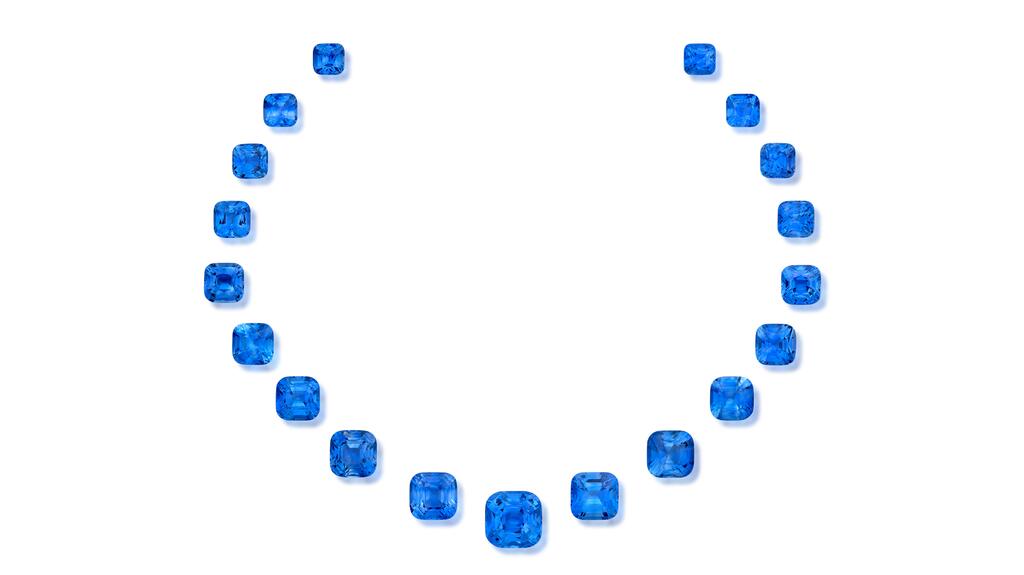

When it comes to sapphires, many consumers are likely to first visualize a classic Kashmir blue.

History, along with mainstream media and pop culture, influence what consumers, many of whom are far removed from the complex business of gemstone trading, believe gems should look like.

When asked about blue sapphire, “[Consumers] most likely tell you that it’s supposed to look like Princess Diana’s sapphire,” says Dussart, who added that the vast majority of the dealers in the trade agree that the beloved British royal’s stone is “too dark.”

Sapphire represents a smaller market value than ruby and emerald, according to Gemfields’ report, and it’s an outlier in the Big Three because it’s available in a rainbow of colors.

The average consumer who assumes sapphires are out of reach for their budget may be surprised at the range of options available to them.

“A lot of sapphires are not that expensive. It depends what color you want,” Dussart says. “A lot of people are exclusively looking at sapphire for the royal blue color … If you’re looking at that, then yes, prices are princess-only department.”

Fine quality, untreated sapphire is still in limited supply, and therefore, pricey. Gemfields’ report stated that its sources indicate that more than 90 percent of sapphires are treated.

New discoveries have been offset by the depletion of existing mines, leading to inconsistency in overall sapphire supply over the last few decades.

Production of the gemstone is relatively stable, though the overall quantity of sapphires available has decreased significantly since the 1980s, according to Gemfields’ report.

Quality is dwindling as well, according to Dussart, and less material is filtering down into the market.

With ultra-high prices for classic blue sapphires posted throughout the Tucson shows in 2024, buyers shifted focus to other shades of blue, opting for teal sapphires from Australia and the earthy, denim-blue material from Montana.

However, several vendors at the 2025 trade shows in Tucson and at the Bangkok Gems & Jewelry Fair in February reported that buyers appear to be leaning back into the Ceylon blue tones.

Not surprisingly, many are still hunting for top-quality material. For these untreated stones, dedicated collectors and investors appear willing to face the sticker shock.

Dealers who have the material are keenly aware that even if they are able to sell, replacing the stone will be a challenge.

Understanding Emeralds

The emerald market has experienced a similar pricing phenomenon in that vendors report buyers looking for untreated fine-quality stones come shopping with apparently no ceiling.

A variety of beryl, emerald has enjoyed a boost from the popularity of green gemstones over the last few years.

It also has become a popular choice for those seeking a colorful engagement ring despite its relative softness (7.5-8) on the Mohs scale when compared with diamonds, rubies, and sapphires.

The emerald mines in Bogotá, Colombia, regarded by many as producing the world’s finest emeralds, have a history dating back more than 800 years, and they’re still producing.

Neighboring Brazil also offers a consistent supply, though it produces less fine quality.

Together with Zambia, these three countries dominate the global emerald supply.

In the last 40 years, there have been no major discoveries that have dramatically changed the emerald supply dynamic.

According to Gemfields’ report, the key factors affecting volume and supply in the last four decades have been changes in mining activities, including a shift towards larger, more mechanized and formalized operations.

However, the finer-quality material is becoming rarer as the appetite for untreated gems grows.

“There [are] not enough stones on the market to support the demand for no-oil gemstones [regardless of origin],” says Zoe Michelou, director at Imperial Colors Ltd., a gemstone manufacturing company based in Bangkok.

“The price has come down a little bit [for commercial-quality goods] because of economic conditions and shifting consumer demand, but it’s widely available,” Michelou says. “I don’t buy much of this quality; I go more toward the high-end quality and here, the price has gone up.”

She says that, at the moment, she can’t even guarantee a customer a price for two months because it keeps climbing.

Michelou’s father, the late Jean Claude Michelou, was an emerald specialist with more than four decades of experience mining the verdant gem, so she’s familiar with the public perception of the gemstone.

“In terms of demand and value in people’s minds, because of the history, Colombia will always be No. 1,” she says, adding that Colombian emeralds command premium prices in the market.

However, Imperial Colors has also established a partnership with a licensed miner in the tribal Swat district in Pakistan, which produces smaller crystals than mines in Colombia.

“They’re extremely clean, the luster is extremely high,” she says.

They’re also highly saturated, and their small size makes the material ideal for calibrated melee.

“I call it the Rolls-Royce of emeralds, because it’s what the [luxury] watch companies are using,” she says. “The price also has gone up, but it remains unstable due to inconsistent production, regional factors, and the limited supply, as the mine is not mechanized.”

While the supply is there, it is still artisanal small-scale mining. There is no dynamite being used on the land and many miners work by hand, meaning the process is slow.

While it is legal for U.S. dealers to trade in Pakistan, working in the country’s remote mining regions means navigating bureaucratic and tribal complexities, making trust-based, established partnerships like Michelou’s an important part of the process.

She also enjoys the look of the lighter-colored emerald material from Russia, she noted, and had some specimens at her booth at the Bangkok Gems & Jewelry Fair.

She said Americans attending the show were intrigued by the material, noting, “I find they are more curious [than attendees from Europe].”

More widely available are the emeralds from Zambia, some of which Michelou says are “even more beautiful than Colombian material.”

The oversupply of commercial-quality goods is impacting this African nation.

In December, Gemfields announced it was temporarily suspending production at the Kagem mine for up to six months.

Five months later, in early May, the company said it would resume “focused” open-pit mining at the site.

The miner’s most recent emerald and ruby auctions held prior to the announcement had yielded lower-than-expected revenues, which it attributed to an oversupply of Zambian emeralds on the market at “discounted prices,” lower production of premium rubies, a weaker luxury market, and civil unrest in Mozambique.

To address these challenges, the miner announced a package of measures designed to cut costs and streamline its business, which included the months-long suspension of mining at Kagem.

However, some say the use of terms like “discounted prices” can give a skewed perception of the emerald market.

Grizzly Mining (the competitor Gemfields is believed to be referring to when it mentions “discounted prices”), which also mines emerald in Zambia, offered a total of 1.93 million carats in its December emerald auction.

Dussart noted that while the volume of material in the Grizzly auction was high, in reality, the proportion of gem-quality material was not.

“Because it was a lot, it looked like the prices went down,” he says, when in fact, prices for the high-end material have not gone down at all.

“If you look at the collections from the high jewelers, there are significantly more emeralds, and so it’s like, emeralds must be all the rage,” he says. “But no, there’s just more emerald right now on the market.”

“Gems, by definition, are freaks of nature. Once you understand that part, you understand that whatever comes out in gem form and gem quality is rare.” — Simon Dussart, Asia Lounges

The Role Brands Could Play

While the luxury jewelry brands once bought only material from top localities—think Colombian emeralds, Ceylon sapphires, and Burmese rubies—they are now a bit more “country agnostic,” according to Dussart, who pointed to Van Cleef & Arpels as an example.

Perhaps, he wonders, the brands are the better way to move the ultra-expensive fine quality material, recalling a recent occurrence with a luxury brand that was looking at an extremely rare, super-clean untreated ruby from Thailand weighing more than 5 carats.

It’s what the trade would refer to as a unicorn stone.

“[The brands] can make phenomenal marketing around it to customers who not only have the firepower to get it but on top of that, don’t have the problem of, ‘Is it going to impact my bottom line next month?’”

The brands have been informed of what is happening at the mines, and they understand the material, the rarity of it, and the sourcing process.

Also, and perhaps more importantly, they understand the psychology of the end buyer and how to educate them.

Color’s Growing Market Share

The colored gemstone market, as a whole, is experiencing a surge in interest.

For years, GemGuide, a trade magazine published by GemWorld International, recognized colored stones as an entire category, usually accounting for somewhere between 9 and 11 percent of the fine jewelry market, but GemWorld International Inc. President Stuart Robertson said in Tucson that isn’t the case anymore.

“We’re seeing color increasing its market share. It’s become a major profit center,” he said during the presentation he co-hosted alongside Branstrator, GemGuide’s editor-in-chief.

There’s a refreshing atmosphere of open-mindedness that has developed amid the increase in demand.

Higher prices across the board are encouraging buyers to embrace cool inclusions, unusual colors, and non-traditional cuts.

Suppliers of the Big Three are learning to ride the wave too.

In 2023, Thailand-based gemstone manufacturer and supplier Navneet Gems & Minerals launched a wholesale line of portrait-cut Mozambican rubies in non-traditional shapes like kites and hexagons, as well as in calibrated cuts.

The initial collection featured material from ruby mining company Fura Gems, and Navneet recently expanded the collection with a deeper-color material sourced from Gemfields’ ruby mine in Mozambique.

The expansive market is even leading some to playfully predict that a new Big Three is on the horizon.

Jason Stephenson, a gemologist at supplier Pala International, wrote in a recent opinion piece for Prism, AGTA’s magazine, that he believes the contenders for the title are rare varieties of garnet, spinel, and Paraíba tourmaline.

People have an appetite for everything beautiful, precious, and rare in general, Dussart says, and those certainly are adjectives that apply to a clean colored gemstone.

“Gems, by definition, are freaks of nature. Once you understand that part, you understand that whatever comes out in gem form and gem quality is rare. It may not be as rare as another, but it’s still rare.”

The Latest

In a 6-3 ruling, the court said the president exceeded his authority when imposing sweeping tariffs under IEEPA.

Smith encourages salespeople to ask customers questions that elicit the release of oxytocin, the brain’s “feel-good” chemical.

JVC also announced the election of five new board members.

With refreshed branding, a new website, updated courses, and a pathway for growth, DCA is dedicated to supporting retail staff development.

The brooch, our Piece of the Week, shows the chromatic spectrum through a holographic coating on rock crystal.

Raised in an orphanage, Bailey was 18 when she met her husband, Clyde. They opened their North Carolina jewelry store in 1948.

Material Good is celebrating its 10th anniversary as it opens its new store in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston.

Launched in 2023, the program will help the passing of knowledge between generations and alleviate the shortage of bench jewelers.

The show will be held March 26-30 at the Miami Beach Convention Center.

The estate of the model, philanthropist, and ex-wife of Johnny Carson has signed statement jewels up for sale at John Moran Auctioneers.

Are arm bands poised to make a comeback? Has red-carpet jewelry become boring? Find out on the second episode of the “My Next Question” podcast.

It will lead distribution in North America for Graziella Braccialini's new gold pieces, which it said are 50 percent lighter.

The organization is seeking a new executive director to lead it into its next phase of strategic growth and industry influence.

The nonprofit will present a live, two-hour introductory course on building confidence when selling colored gemstones.

Western wear continues to trend in the Year of the Fire Horse and along with it, horse and horseshoe motifs in jewelry.

Rossman, who advised GIA for more than 50 years, is remembered for his passion and dedication to the field of gemology.

Guthrie, the mother of “Today” show host Savannah Guthrie, was abducted just as the Tucson gem shows were starting.

Butterfield Jewelers in Albuquerque, New Mexico, is preparing to close as members of the Butterfield family head into retirement.

Paul Morelli’s “Rosebud” necklace, our Piece of the Week, uses 18-karat rose, green, and white gold to turn the symbol of love into jewelry.

The nonprofit has welcomed four new grantees for 2026.

Parent company Saks Global is also closing nearly all Saks Off 5th locations, a Neiman Marcus store, and 14 personal styling suites.

It is believed the 24-karat heart-shaped enameled pendant was made for an event marking the betrothal of Princess Mary in 1518.

The “Kering Generation Award x Jewelry” returns for its second year with “Second Chance, First Choice” as its theme.

Sourced by For Future Reference Vintage, the yellow gold ring has a round center stone surrounded by step-cut sapphires.

The clothing and accessories chain announced last month it would be closing all of its stores.

The “Zales x Sweethearts” collection features three mystery heart charms engraved with classic sayings seen on the Valentine’s Day candies.

The event will include panel discussions, hands-on demonstrations of new digital manufacturing tools, and a jewelry design contest.