McCormack looked to the 19th century’s “golden age” of astronomy when designing her new celestial-themed collection.

Chain of custody challenges for colored gems

Gemologist Edward Boehm details efforts being made worldwide to improve the lives of small-scale, or artisanal, colored gemstone miners, including a project he helped with in Madagascar.

Colored gemstones have enjoyed record-breaking auction prices due to a strong resurgence in demand over the past six years. Though colored gemstone prices are not as easy to track, historically they tend to follow diamond and gold price trends. Recently however, colored gems have shown greater gains than diamonds due to the dramatic drop in diamond demand coupled with overproduction at the beginning of the global recession in 2008. Gems have also outperformed gold as it has recently lost its luster as a haven for hedging stock investments.

Naturally, this trend has brought much more attention to colored gemstones and their sources, as well as how they are mined, cut, and traded.

Unlike the diamond industry, colored gemstones do not have an industry-wide system in place to promote ethical trade of rough gem material. This is largely due to the fact that most colored gemstones are difficult to trace because they are mined by small-scale artisanal miners while most diamonds are mined by large-scale mining concerns.

In May of 2000, South African diamond producing countries initiated discussions on what became known as the Kimberly Process to stop the trade of rough diamonds that could potentially be used to finance rebels seeking to undermine legitimate governments.

In 2003, this process was implemented by several diamond-producing countries, and today has 54 members from 80 countries that represent approximately 99.8 percent of global diamond production. Essentially, the process seeks to provide a certification scheme by which supplier countries are required to meet strict guidelines to guarantee conflict-free diamonds through greater transparency and exchange of detailed information related to mining, recovery and transportation of rough diamonds. However, in December 2011, international non-governmental organization Global Witness resigned as an official observer to protest what it called “blatant breaches” in compliance by several supplier member countries.

Gemstone mining can be divided into large-scale, small-scale, and artisanal mining operations. For simplicity most organizations combine small-scale and artisanal into one category. According to The World Bank, “at least 20 million people engage in artisanal and small-scale mining and a further 100 million people depend on it for their livelihood. These numbers are growing in line with higher prices and demand for minerals both in OECD countries and emerging economies such as China and India.”

There are 47 primary colored gemstone producing countries around the world. Approximately 20 percent of all colored gemstones come from large-scale mining operations (LSM) while approximately 80 percent come from artisanal and small-scale mining operations (ASM). It is estimated that 90 percent of these ASM operations are located in developing and emerging countries. In comparison, approximately 10 percent of all diamonds come from ASM operations.

The colored gemstone industry has made numerous proposals for certification schemes but none have taken hold.

In 2001 the World Bank launched an initiative called the Communities, Artisanal and Small-Scale Mining (CASM) declaring that “CASM’s holistic approach to small-scale mining aims to transform this activity from a source of conflict and poverty into a catalyst for economic growth and sustainable development.” The key words here are “sustainable development,” which point to the need for creating working conditions and environmental practices that are sustainable for future generations to enjoy. If the goal is sustainability then most of the social, economic and environmental concerns that these small-scale mining communities face can be addressed and resolved over time. Since a majority of these ASM communities are located in remote areas within developing countries, they struggle with health care, mining safety, water supplies, fair compensation, education, housing, etc.

One such initiative that was supported by the World Bank was a project in Madagascar to help improve and modernize their gemstone mining sector. I personally worked indirectly on this project as a consultant to USAID who was assisting the World Bank in assessing the needs within the gemstone mining sector.

The problem Madagascar faced was that it produced large quantities of colored gemstone rough that were mostly being smuggled out of the country with little benefit to the local mining communities. The goal was to reduce domestic poverty by creating opportunities for added value within mining communities in Madagascar.

The World Bank ultimately supported the Ministry of Mines of Madagascar Mineral Resources Governance Project with a $40 million grant from 2003 to 2010. This initiative modernized mining law and regulations, created a mining institution, established a gemological institute, developed local gemstone cutting, and promoted all aspects of mining and community development. Though internal politics reduced the scope of the project benefits, it is still regarded as an example of what could be accomplished in developing supplier countries.

Beyond World Bank-sized initiatives; there are smaller programs that have been implemented by individual colored gemstone mining concerns, dealers and retailers. The International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA), CIBJO - The World Jewellery Confederation, and the American Gem Trade Association (AGTA) have promoted such programs among its members of miners and colored stone dealers and retailers. These organizations have been actively involved in numerous conferences regarding ASM issues and global initiatives to improve ethical trade and sustainability. Three of ICA’s members, the Tanzanite Foundation, Gemfields and the Belmont Group are examples of relatively large-scale colored gemstone mining ventures that are dedicated to fair trade as well as socio-economic and environmental sustainability.

The Tanzanite Foundation is a nonprofit entity formed in 2003 by Tanzanite One, which operates a large-scale tanzanite mining operation in Merelani, near Arusha, Tanzania. A portion of all its sales go toward funding the foundation. The Tanzanite Foundation website states that it is “dedicated to protecting and promoting tanzanite. It acts on behalf of all ethical and socially responsible operators and partners in the tanzanite industry and implements standardized methods of practice and conduct. The Foundation seeks to deliver a truly ethical route to market in accordance with the Tucson Tanzanite Protocols.”

Gemfields, with deep roots in mineral resources, is a relative newcomer to gemstone mining. It is a publicly traded company with controlling interests in the Kagem emerald mine in Zambia and a ruby mining venture in Mozambique. Their global mine-to-market campaign promotes traceability as well as fair and ethical trade and environmental sustainability. Their website states that their “dedication to preserving the environment, nurturing relationships with local communities and upholding human rights remains paramount to our success.” They also support the World Land Trust in providing support for conservation projects in Africa. Gemfields only sells rough material to its network of cutters around the globe.

Belmont is a family-owned large-scale emerald mine that strives to not only meet but exceed strict new Brazilian environmental laws. Though their operation is considered large scale for colored gemstone mining, it is still relatively small when compared to large-scale diamond mining.

High-pressure water, used for separating gem material from the ore, is recycled through an extensive natural filtration system. Soil and trees removed during the mining process are replaced as the land is prepared to be fully reclaimed to its original state. Miners are equipped with modern equipment and follow strict safety procedures. They also receive fair pay, health care and even a hearty daily lunch, which I had the pleasure to share with one of the shifts.

So far there are still only a few wholesalers who actively are pursuing fair and ethical trade initiatives but many are discussing how they should move forward. The lack of a large-scale leader has made it difficult for the wholesalers to organize a coordinated effort. There are a few larger companies like the Tanzanite Foundation, Gemfields and Belmont that have set a positive example that others will hopefully follow.

The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) has a certification program that sets standards for what it deems are responsible business practices for companies in the jewelry supply chain, ranging from mining to retail. Their initial focus has been on the precious metals supply chain but they will certainly branch out into other sectors as they become more relevant. Their chain-of-custody standards require that the materials be conflict-free as a minimum, and responsibly produced.

Momentum seems to be developing for a viable mine-to-market system of sustainable trade for colored gemstones as more attention is directed at this sector. However, the vast complexities associated with artisanal small-scale mining will continue to hinder progress. An efficient and fair system will require that all sectors of the industry be included in a transparent and inclusive manner.

The development of such a system, that all levels of the supply chain will support, will be essential for its long-term success. In the meantime, miners, dealers and retailers should focus on providing any help to these communities in any way they can -- simple projects to help find water supplies, build schools, supply books, basic gemological training, first aid provisions, mining equipment and safety instruction, mosquito netting, support land reclamation projects, etc. Implementing these small projects will be difficult but our future depends on sustainability as well as ethical trade so future generations can also enjoy these rare and precious creations of nature.

Edward Boehm is the founder and president of RareSource in Chattanooga, Tenn., a company specializing in fine and collectable gemstones, collection sales and acquisitions and museum consulting. He began his gemological studies in Switzerland under the tutelage of his grandfather, Edward J. Gübelin, graduated in geology and German from the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, and later obtained a graduate gemologist diploma from the Gemological Institute of America and a certified gemologist title from the American Gem Society. He has worked for the Gübelin Gem Lab in Lucerne, Switzerland, was a museum and laboratory consultant to the GIA, and consulted for USAID as part of a World Bank-sponsored initiative to improve the gemstone sector in Madagascar. His current work takes him to mining localities around the globe as a consultant and buyer.

The Latest

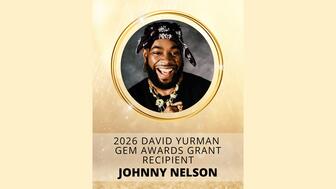

Nelson will be honored as the inaugural grant winner at the Gem Awards gala on Friday.

The new smart design software allows jewelers to configure, price, and confirm a custom engagement ring in real time for in-store customers.

Every jeweler faces the same challenge: helping customers protect what they love. Here’s the solution designed for today’s jewelry business.

The 10,000-square-foot diamond manufacturing facility officially opened in late February and employs 50 people.

The MJSA Education Foundation’s scholarships support students pursuing jewelry careers.

The largest white diamond to come to market in the U.K. in more than a decade, the VVS1, I-color stone is expected to top $1 million.

With refreshed branding, a new website, updated courses, and a pathway for growth, DCA is dedicated to supporting retail staff development.

Skelly shares her plans for reimagining the fine jewelry retailer she re-acquired after it faltered last year.

The collection takes inspiration from the emotional space between people, moments, and experiences.

In 2026, the jewelry retailer is celebrating a milestone only a small percentage of family-owned businesses survive to see.

The group of jewelers held a jewelry raffle in support of the Children’s Hospital of Richmond at VCU.

The jewelry giant released preliminary results for the fourth quarter and full year on Monday, with final results slated to come next week.

The retailer also gave an update on its vendor partnerships.

The award-winning actress is the “epitome of modern allure,” the brand said.

The “Bloom” collection draws from the flower power movement of the 1960s and ‘70s with inlay pendants offered in eight colorways.

The unique piece was one of the custom works offered at the foundation's recent silent art auction, which garnered nearly $15,000 in total.

Bulgari named Gyllenhaal as its brand ambassador for his embodiment of artistic depth, intellectual curiosity, and warmth.

Awards were given to four students, one apprentice, and an emerging jeweler.

The top jewelry lot of the late model’s estate sale, hosted by John Moran Auctioneers, was an Oscar Heyman & Brothers for Cartier necklace.

Moses, who started at GIA’s Santa Monica lab in 1976, will leave the Gemological Institute of America in May.

Increased competition, falling lab-grown diamond and moissanite prices, and the rising cost of gold took a toll on the moissanite maker.

The earrings, our Piece of the Week, feature pink tourmalines as planets orbiting around an aquamarine center set in 18-karat rose gold.

“The Price of Freedom” campaign video for International Women’s Day confronts the quiet violence of financial control.

Also, a federal judge has ordered that companies that paid tariffs implemented under the IEEPA are entitled to refunds.

The ever-growing collection, which just expanded with the addition of Olga of Kyiv, features cameos of 12 women from history.

We asked a jewelry historian, designer, bridal director, and wedding expert what’s trending in engagement rings. Here’s what they said.