Q&A: Constance Polamalu on Selling Natural and Lab-Grown Diamonds

The jeweler shared her change of heart on lab-grown diamonds and why she keeps them separate from natural diamonds in her business ventures.

She’s the chief operating officer at Zachary’s Jewelers in Annapolis, Maryland. She’s also the designer behind fine jewelry brand Birthright Foundry.

Lastly, she’s the owner of Bloomstone Jewelers, a lab-grown diamond boutique also located in Annapolis.

In the first two roles, Polamalu works exclusively with natural diamonds, while Bloomstone specializes in lab-grown stones.

In a recent interview with National Jeweler, she shared how the businesses align, when and why she changed her mind about lab-grown diamonds, and why she chose to keep natural and lab-grown stones separate.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Lenore Fedow: I’m familiar with your roles at Zachary’s Jewelers and Birthright Foundry, but not with your latest venture. Can you tell me more about Bloomstone?

Constance Polamalu: Bloomstone Jewelers is an exclusively lab-grown diamond store. It was conceived when I was doing some SWOT analysis for my other businesses.

LF: What is a SWOT analysis?

CP: SWOT analysis is [looking at] strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats. Lab-grown diamonds had come up as a threat to my natural diamond businesses. And so I started really digging, and I wanted to know more; I wanted to know how it was being sold and how it was being positioned.

I felt like there was an opportunity there, which I think happens a lot when you look at weaknesses.

You can have weaknesses or threats. How you address them can turn into an opportunity, and that’s what happened with Bloomstone.

I saw an opportunity with lab-grown, but it didn’t make sense to me to bring lab grown into Zachary’s or to work with it for Birthright because I think they’re two very different offerings for different clients, but they’re underpinned by the same human desire to have something beautiful, sparkly, and enduring.

LF: There are a lot of strong industry opinions about lab-grown diamonds. How would you describe their place in the jewelry world?

CP: I would say that to understand the lab-grown position in the world, we have to take off our jeweler hats, put on our consumer hats and take a look at what people are facing and what matters to people.

Just like a good buyer doesn’t buy just what they like for a store, a great buyer is going to buy what they see fitting and working for the people they serve.

It’s very similar with natural and lab grown. I think it’s important that we stop this diamond civil war, for both sides.

Lab-grown diamonds still survive because of this desire for diamonds. We are somehow inherently connected to diamonds, and I think it has to do with sunlight and our desire for strength and stability, the things that are properties of diamonds and, scientifically, properties of lab-grown diamonds as well.

I think what we see is a desire for access globally. People have access to things via social media. So, as a global economy, our young people are growing up knowing that other things exist.

Twenty years ago, pre-social media or at the early onset of social media, people didn’t know there were others in the world walking around with 5-carat diamonds on. Now they do and now they want to know, ‘how can I experience that? How can I feel that glamorous?’

Lab grown is an answer for that. It’s just like how Airbnb is an answer for your dream vacation if you don’t have the means to own a vacation home. The desire [for lab-grown diamonds] comes from a desire to be included.

[We don’t want to] accidentally alienate people and start a class war against diamonds because that’s the risk that we run if we continue telling people that one or the other is bad.

Either side can sink this whole ship for everyone.

LF: As a retail reporter, my perspective always has been that it has to be less about preference and more about consumer education. For a consumer, the problem arises when people don’t understand what they’re buying. When you’re dealing with your customers at Bloomstone, how do you incorporate that education?

CP: Part of the reason why it was so important to me to open a separate business is because I think one of the largest problems is disclosure and navigating that.

By drawing very clear boundaries and saying, this is where we sell natural diamonds and this is where we sell lab-grown diamonds, the customer already is making a little bit of a decision before walking into either store. That removes some of the burden from my staff in either space.

I try to train all of my people to be very fact based.

Lab-grown diamonds are scientifically diamonds, but because they’re a technology and not a commodity, the pricing is very different. Technology pricing tends to be more incrementally based and commodity pricing is always going to be exponentially based.

We share that with people, and we ask them to make their own decisions.

When they ask us if it’s a good investment, that’s a tricky one because you have to define investment. Is this a good investment like buying land? No, neither [natural nor lab-grown diamonds] are.

That’s a conversation I think we’ve mistakenly made a part of jewelry buying for a long time.

I say, one has a history of holding value, and that would be natural diamonds. Even though right now we’re at a down point, in the end, I believe that it will correct.

As a technology, I can’t promise you that [with lab-grown diamonds]. I can’t speculate on what’s going to happen with the value of lab grown. It’s purely what you make of it.

Sometimes people will say, “I just don’t think it’s as meaningful to have a lab-grown diamond.”

And to that, I would challenge people and say, “I have a lot of costume jewelry from my grandmother. It has no value other than it was my grandmother’s.”

It’s allowing people to assign their own meaning and value to what they’re purchasing. I want them to do that without judgment. [With] judgment calls, we alienate people.

If we discern that something may not be right for our particular business, that’s OK. As a businessperson, I don’t see it working [at Zachary’s or Birthright Foundry]. What’s working there is already working. Leave it alone.

But there is opportunity for lab-grown business and for lab grown to be sold in a different way than I saw it being sold anywhere else.

“If they’re strong natural [diamond] proponents, they don’t stay in the [Bloomstone Jewelers] very long, which I think is actually a benefit to everyone involved.” — Constance Polamalu

LF: That’s interesting. I often wonder how a lot of these intra-industry conversations about lab grown and natural transfer over to the real world when you’re actually at a counter with a customer. Do your customers at Bloomstone express any concerns about buying lab grown over natural?

CP: I would say if they’re strong natural proponents, they don’t stay in the store very long, which I think is actually a benefit to everyone involved.

They don’t waste any of their time or my staff’s time. There’s just no need to convince somebody of the decision they’ve already made.

For me, that was something I had to learn because early into the lab-grown conversation, I was very against it. I didn’t understand it. I didn’t understand why people would want it. It just seemed scary and threatening and aggravating.

I was ready to duke it out with people. And then I started to realize, this is wrong and I’m feeling aggressive about this because of my personal perspective here. If I remove myself and I think about what’s best for the person standing across from me, yeah, I can understand.

Now, I need to be very clear about what they’re buying and what the value propositions are for either, but I think we have to trust that our consumers, if given all the information, are going to make their own decisions.

I also wanted to make sure that I was presenting something that wasn’t greenwashing. I really didn’t like the way a lot of lab-grown companies were coming into the space suggesting they were the eco-friendly option when what I know to be true is that there are nuances to everything.

LF: Do you find that customers come to you with the idea in their head that they are making a more eco-friendly choice?

CP: Yes. There’s been a lot of damage done and a lot of misinformation spread.

People talk about how AI is going to change business and creative things. For me, the biggest thing [to note] is that it’s only capable of repeating what it reads. And if it reads the same information, whether it’s right or wrong, 400 times, it’s going to say that that is the answer.

So that’s where if you feel like you owe the world honest answers, you have to give them. But more people have to get on board with telling the truth, or at least telling their truth, if they want to have a say on it.

LF: Can you tell me about your customer base at Bloomstone versus in your different roles where you sell natural diamonds? Does one skew younger, and the other older?

CP: Honestly, no. The makeup is probably very similar, age-wise.

There are more women in Bloomstone, but that could also be because of how we’ve designed the store and how we market it.

I think a lot of people, when I talk to them, are surprised to hear that I have just as many customers in their late 70s as I do in their 20s.

LF: Do you have customers who will buy from Birthright Foundry and then will also buy something at Bloomstone?

CP: I do. People have been really confused about why I’m doing this and why I have three separate things going on. I liken it to, if I were a chef or a restauranteur, it probably wouldn’t be so weird, right?

Zachary’s Jewelers would be our upscale steakhouse where people have a tendency in town to go and celebrate special occasions. It feels really fancy and elevated. It feels familiar.

Bloomstone Jewelers would be my spin-off chic taco bar where people tend to go for happy hours and a little bit more casual fare.

And then Birthright Foundry would be my Omakase sushi spot. It’s not for everybody. It’s exclusive, but for those who know, they know.

And if I had three restaurants, some people would only eat at one of those restaurants, some people would eat at all three, and some would only eat at two of them.

LF: That’s a good way to look at it. That’s an interesting perspective.

CP: If we look outside our industry, there’s a lot of precedent for all of this. Sometimes we spend so much time looking at, what are these other jewelers doing? or what are my competitors doing? as opposed to just looking for use-case scenarios outside [the jewelry industry] and bringing them home.

LF: We’re at my last question. It seems like for you, lab-grown and natural diamonds work best as separate businesses. Do you think they can coexist in one environment?

CP: I definitely think they can. There’s a heavy burden on the jewelers who are trying to keep them coexisting that I just didn’t want, frankly.

It sounds cleaner and easier to set the expectations for customers the second they walk in the door, rather than to bring them in and woo them and then try to figure out what made sense to them after the fact, especially with the way that the industry has gone in the last five years.

Down the line, would I wrap Bloomstone into Zachary’s? Maybe, but right now; we’ve seen this really tumultuous pricing structure and margins in the last five years, and that was a challenge I just didn’t want to take on.

It seemed like something that wasn’t right for me because I think that when lab-grown came in early on and people were able to make a ton more money, we had some people in the industry pushing lab grown in their stores because it was better for them.

Now that the pricing has really come out from underneath lab grown, if you were used to selling it at 20 back from Rap, making a killing on it, and now it’s $1,200 a carat, you might be more inclined to push people back to natural. I know I would. I didn’t want that internal struggle because I felt like that might affect relationships with customers.

I think if you’re up for that challenge and you have a really good plan, absolutely, they can exist in the same store.

The average price point of a store is going to make a difference too. We all have different sweet spots, and there are probably some [stores] that are different from mine where it makes more sense to offer both and give people that option.

The Latest

Chicago police and members of the U.S. Marshals Service tracked down the 35-year-old suspect earlier this week in St. Louis.

Owners of the Ekapa Mine reportedly filed for liquidation about a week after a mudslide trapped five workers who have yet to be found.

A 10-year alliance has also begun to address the shortage of bench jewelers through scholarships, enhanced programs, and updated equipment.

Every jeweler faces the same challenge: helping customers protect what they love. Here’s the solution designed for today’s jewelry business.

The “Splendente” collection has evolved to feature hardstone letter pendants, including our Piece of the Week, the onyx “R.”

The jewelry collection belonged to “one of society's most glamorous and beautiful women of the mid-20th century,” said the auction house.

The update came as Anglo took its third write-down on the diamond miner and marketer, which lost more than $500 million in 2025.

With refreshed branding, a new website, updated courses, and a pathway for growth, DCA is dedicated to supporting retail staff development.

Emmanuel Raheb discusses the rise of “GEO” and the importance of having well-written, quality content on your website.

Each received around four years for burglarizing a jewelry store and a coffee shop in Simi Valley, California, last May.

Catherine Aulick, a GIA graduate, received the ninth and final Gianmaria Buccellati Foundation Award for Excellence in Jewelry Design.

We asked a jewelry historian, designer, bridal director, and wedding expert what’s trending in engagement rings. Here’s what they said.

Experts from India weigh in the politics, policies, and market dynamics for diamantaires to monitor in 2026 and beyond.

Beth Gerstein discusses the vibe of the new store, what customers want when fine jewelry shopping today, and the details of “Date Night.”

Are arm bands poised to make a comeback? Has red-carpet jewelry become boring? Find out on the second episode of the “My Next Question” podcast.

The Swiss watchmaker is battling declining sales amid a rapid retail expansion, according to a Financial Times report.

The campaign celebrates Giustina Pavanello Rahaminov, the co-founder’s wife and matriarch of the family-owned brand, for her 88th birthday.

Rachel Bennett, a senior jeweler who has been with Borsheims since 2004, earned the award.

After the Supreme Court struck down the IEEPA tariffs, President Trump imposed a 10 percent tax on almost all imports via a different law.

The industry veteran, who was with The Edge Retail Academy for 14 years, joins her husband at the company he founded in 2022.

The vintage signed jewelry retailer chose Miami due to growing client demand in the city and the greater Latin American region.

Former Flight Club executive Jin Lee will bring his experience from the sneaker world to the pre-owned watch marketplace.

Sakamoto, who died in mid-January following a sudden illness, is remembered for his humility and his masterful, architectural designs.

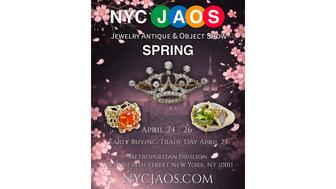

The April event will feature a new VIP shopping day requiring a special ticket.

Bulgari chose the British-Albanian singer-songwriter for her powerful and enduring voice in contemporary culture, the jeweler said.

In a 6-3 ruling, the court said the president exceeded his authority when imposing sweeping tariffs under IEEPA.

Smith encourages salespeople to ask customers questions that elicit the release of oxytocin, the brain’s “feel-good” chemical.

![“There is greater acceptance [of lab-grown diamonds] today, but manufacturers had to put in a lot of effort to make it happen,” said Smit Patel, director of finance for lab-grown diamond company Greenlab, whose factory in Surat, India, is pictured. Greenlab lab-grown diamond factory in India](https://uploads.nationaljeweler.com/uploads/5d145d435434011afc43a4f507ebaefd.jpg)