What I Learned Following the Veins of East Africa’s Mines

Senior Editor, Gemstones, Brecken Branstrator shares takeaways from her second trip to Tanzania and Kenya.

I know how lucky one trip makes me. Two is a gift I wouldn’t have expected, but it provided me with another amazing opportunity to go to gem-sourcing areas and see how much has changed since I last visited in January 2016 with a group organized by Roger Dery.

It’s such an important region for our industry, and it’s an interesting time for both countries in regard to their gem trades.

In that vein, I wanted to share some of what I observed on my second trip to East Africa.

Tanzania continues its efforts toward value addition

When I traveled to Tanzania in 2016, there was not yet a wall around the tanzanite mining area; former Tanzanian President John Magufuli would construct it a year later to regulate activity.

The area is comprised of four mining blocks—we heard an estimate of 400 mines among them—one of which is where our group went for a visit to the Merisheki mine, owned by Roger’s longtime friend and miner Sune Merisheki.

Entering the wall required a lot of planning and preparation for our hosts in terms of getting our information, visa, and passports to the government ahead of time to get permission for our visit.

It required a police escort and, on the way out, a pat down from security to prevent smuggling.

It was well worth it for the chance to go behind the wall to not only see the scope of mining activity but also for the opportunity to enter one of the mines—Sune was nice enough to let us go underground.

Led by his son, Bjorn Merisheki, and with a lot of help from their mine workers, we went down more than 300 feet, ending at a spot where they hit a pocket so they could show us the vein they were following and point out the mineral indicators.

With steep steps and just headlamp lighting, it was a fairly grueling trip down and back, but one I would do again and again because nothing beats that firsthand experience to help understand the science behind mining and, more importantly, see what the miners endure to recover gemstones.

When it comes to tanzanite, all buying and cutting activity has to be done within Merelani town, and finds have long had to be registered with government officials.

The wall might represent the most concrete example of Tanzania’s move toward beneficiation, but it’s hardly the only one.

In another big move in 2018, the Tanzanian government put a ban on the export of all rough stones from the country to try get the cutting and polishing done in-country before being sold elsewhere.

The ban brought much of the country’s market to a temporary halt as it wasn’t equipped to suddenly cut that much material.

Today, Tanzania bans the export of more than a half-dozen gemstones when they weigh more than 2 grams (10 carats) in rough form: ruby, sapphire, emerald, garnet, spinel, tanzanite, and alexandrite.

Gemstone trading activity also has been moved to one area in Arusha.

Given the country’s current importance in the colored stone trade, it will be interesting for everyone involved to watch what other moves the Tanzanian government makes.

Kenya’s drawing inspiration from its neighbor

It seems Kenya has taken notice of Tanzania’s efforts to keep its mineral wealth in-country.

While in Voi, Kenya, I had the chance to go to the new Voi Gemstone Center, created for the purpose of value addition and offering gemstone identification services, faceting equipment, places for buying, selling, and trade fairs, training for the industry, and even help with exporting stones.

Taita-Taveta is the most important area for gem mining and trading in Kenya, with about 5,000 mines in the area, according to one official.

Bjorn and his wife, Rachel Merisheki, were meeting with Edward Omito from the Ministry of Mining and were nice enough to let me listen in on their chat about the center and the area’s progress and what work still needs to be done.

Edward seemed genuinely excited for the potential of the center, which was created to make business easier for members of the gem trade in Taita-Taveta, but he noted at the time of my visit in late July they were still waiting for the president to commission it for activity to really get going.

Indeed, while he was nice enough to give me a tour of the space, it was pretty empty when we walked around, with no booths for trading set up and only a few people using the equipment.

Interestingly, he said they got the idea for the center from Tanzania and how it was working to create a process in-country for tanzanite.

They want to eventually expand to have open-air markets in Voi, he added, potentially inviting buyers from other countries to visit and do business.

Edward did note when we were there, though, that the center has been a political project of the president. At the time of our visit, we were just ahead of an election, and he seemed very aware that the center’s future was dependent on the election results.

William Ruto, formerly Kenya’s deputy president, was declared the new president in August.

The Voi center seems like it could make a difference in the Kenyan market, so let’s hope it doesn’t lose steam before it’s had the chance to get off the ground.

How gemstone mining is changing a lifestyle

One of my favorite parts of both trips was a visit to the Kitarini Primary School for children of Maasai miners, not only for the chance it provided to meet and interact with its students but also because it’s an interesting look at a changing lifestyle spurred by gemstone mining.

The school has grown drastically since I was there in 2016, thanks to the hard work of the Merisheki family, the Dery family, Gem Legacy’s efforts to raise money for various initiatives, many other members of the trade, and of course the school’s amazing staff doing everything they can to meet the challenges that arise for their students.

There were several new buildings when I went back this time, and the student body had more than doubled to nearly 950 students.

The school’s focus now is on building additional teacher housing so they can attract and hire more faculty and, eventually, adding more classrooms.

Our group had some incredible experiences while we were there, participating in an activity day that had us spending an entire school day with the children and getting to see several student performances of traditional Maasai dances.

The school is in the Longido district, north of Arusha, an area rich with ruby-in zoisite. (The area also produces some gem-quality rubies but not in large numbers.)

It’s also located firmly in Maasailand, which presents its own obstacles for those trying to build the school—the Maasai are semi-nomadic and pastoral, meaning they live by herding cattle and goats. This includes herding done by their kids, leaving little time for traditional schooling.

For Kitarini, this has meant issues getting students to come back regularly, especially when it requires long walks to and from or during the lunch hour prior to setting up a lunch program.

But this is also what makes their success so amazing—a group of people who traditionally have moved around are now staying still for the chance to find gemstones.

There were several moms on the school board—also part of the Maasai tribe—who spoke with us about wanting to get involved as they realized how important it was for their kids.

What an interesting thing, to see gemstone mining influencing such a thing.

Miner challenges there are similar across the board

We visited six mines during the trip, all but one in Kenya, and what struck me was when asked what they most struggled with at their mines, the miners all gave same answers: a lack of water, food, and/or equipment.

For many of them, the rainy season also brought issues of flooding and how to redirect the rainwater away from their mines.

You really only need to see one mine in the bush of Africa to understand how hard their work is and what they deal with for just the hope of finding a stone.

There were also several mentions about one ongoing issue affecting the mining world: the need for more education about the gemstones being mined and their value.

GIA has tried to address this issue, for example, with its creation and distribution of a gem guide for artisanal miners, and it’s something Edward Omito also said he hopes to help alleviate with the Voi center when it opens.

Many of the experiences we had on our trip kept bringing a crucial part of the conversation around responsible sourcing and transparency to my mind—the importance of keeping a local perspective, going directly to the miners and traders and asking what is needed, rather than assuming or trying to solve issues that aren’t there.

If the importance of providing such help to those at the first step of our supply chain isn’t immediately obvious, you’d only need to visit one mine for that clarity as well—each and every person we met had such immense pride in the work they were doing.

The miners couldn’t wait to share their stories with us and show us their mines.

In so many cases, I swear they would’ve happily sat there the whole day talking about mining or going inside the mine with us, showing us how far they’ve gotten and the veins they were now following.

I still can’t believe I got the chance to have such an adventure a second time.

It’s a trip I wish everyone in the industry, regardless of their role in the trade, would get the chance to take because, cliché as it may sound, it’s truly life-changing and eye-opening.

Now that there’s so much of a focus on responsible sourcing at each point in the supply chain, it also makes me hopeful for the direction in which we can all head together.

*Editor’s note: Two captions were updated to reflect that Kamtonga and Mwatate are in Kenya.

The Latest

Raised in an orphanage, Bailey was 18 when she met her husband, Clyde. They opened their North Carolina jewelry store in 1948.

Smith encourages salespeople to ask customers questions that elicit the release of oxytocin, the brain’s “feel-good” chemical.

Material Good is celebrating its 10th anniversary as it opens its new store in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston.

Launched in 2023, the program will help the passing of knowledge between generations and alleviate the shortage of bench jewelers.

The show will be held March 26-30 at the Miami Beach Convention Center.

The estate of the model, philanthropist, and ex-wife of Johnny Carson has signed statement jewels up for sale at John Moran Auctioneers.

Are arm bands poised to make a comeback? Has red-carpet jewelry become boring? Find out on the second episode of the “My Next Question” podcast.

Criminals are using cell jammers to disable alarms, but new technology like JamAlert™ can stop them.

It will lead distribution in North America for Graziella Braccialini's new gold pieces, which it said are 50 percent lighter.

The organization is seeking a new executive director to lead it into its next phase of strategic growth and industry influence.

The nonprofit will present a live, two-hour introductory course on building confidence when selling colored gemstones.

Western wear continues to trend in the Year of the Fire Horse and along with it, horse and horseshoe motifs in jewelry.

![A peridot [left] and sapphires from Tanzania from Anza Gems, a wholesaler that partners with artisanal mining communities in East Africa Anza gems](https://uploads.nationaljeweler.com/uploads/cdd3962e9427ff45f69b31e06baf830d.jpg)

Although the market is robust, tariffs and precious metal prices are impacting the industry, Stuart Robertson and Brecken Branstrator said.

Rossman, who advised GIA for more than 50 years, is remembered for his passion and dedication to the field of gemology.

Guthrie, the mother of “Today” show host Savannah Guthrie, was abducted just as the Tucson gem shows were starting.

Butterfield Jewelers in Albuquerque, New Mexico, is preparing to close as members of the Butterfield family head into retirement.

Paul Morelli’s “Rosebud” necklace, our Piece of the Week, uses 18-karat rose, green, and white gold to turn the symbol of love into jewelry.

The nonprofit has welcomed four new grantees for 2026.

Parent company Saks Global is also closing nearly all Saks Off 5th locations, a Neiman Marcus store, and 14 personal styling suites.

It is believed the 24-karat heart-shaped enameled pendant was made for an event marking the betrothal of Princess Mary in 1518.

The AGTA Spectrum and Cutting Edge “Buyer’s Choice” award winners were announced at the Spectrum Awards Gala last week.

The “Kering Generation Award x Jewelry” returns for its second year with “Second Chance, First Choice” as its theme.

Sourced by For Future Reference Vintage, the yellow gold ring has a round center stone surrounded by step-cut sapphires.

The clothing and accessories chain announced last month it would be closing all of its stores.

The “Zales x Sweethearts” collection features three mystery heart charms engraved with classic sayings seen on the Valentine’s Day candies.

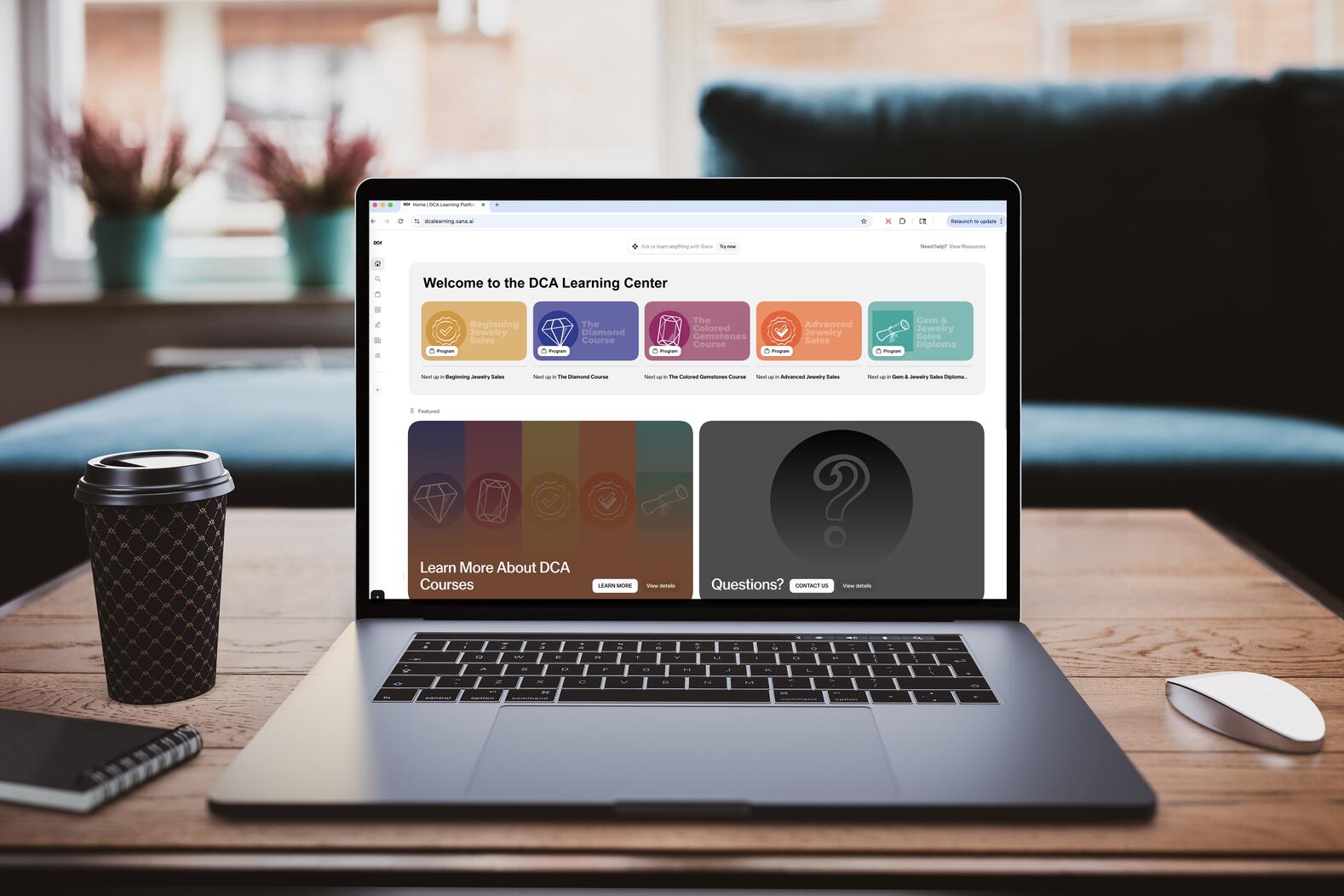

The event will include panel discussions, hands-on demonstrations of new digital manufacturing tools, and a jewelry design contest.

Registration is now open for The Jewelry Symposium, set to take place in Detroit from May 16-19.