5 Interesting Facts You Might Not Know About Diamonds

Editor-in-Chief Michelle Graff recaps a webinar in which she learned more about the stones’ formation, inclusions and the oldest diamonds on Earth.

I had a great deal of fun doing it, and it served as a much-needed reminder of how much I like to just write, not necessarily about a controversy or a lawsuit, or with clicks in mind, but just for the sheer pleasure of finding an expressive way of sharing something I enjoy.

With that in mind, I’m having fun again this week, this time by sharing five facts about diamonds gleaned from a webinar.

On Thursday, geologist Evan Smith, a research scientist at the Gemological Institute of America, held the first in what is going to be a series of online “Knowledge Sessions” presented by GIA.

The webinars will feature presentations on gemology from scientists, field gemologists and educators, continuing next Thursday with Mike Breeding, GIA senior research scientist, talking about identification methods for lab-grown diamonds.

(GIA is currently building a web page for its Knowledge Sessions; we will share it as soon as it is available.)

Smith’s talk, “The Unique Story of Natural Diamond,” focused on what makes the hardest substance on Earth—and one of the world’s most popular gemstones—so interesting to geologists.

I’ve interviewed and written about Smith’s research here and there over the years; he was the lead author of an article on blue diamonds that landed on the cover of Nature, a scientific journal, in 2018, and his diamond research made the cover of Science in 2016.

He alluded to both these studies in his presentation and taught me a few new things about diamonds as well.

Please feel free to comment below if you’ve learned anything, or if you just feel like saying hello. You also can view the presentation in its entirety on YouTube.

1. Diamonds form deeper in the earth than other minerals.

Most minerals including corundum (ruby and sapphire) and beryl (emerald, aquamarine and morganite) form in the Earth’s crust, which is the layer upon which we all live.

But not diamond, which Smith said is “completely exotic … because it is formed much deeper in the Earth,” beneath the crust at depths of 150-200 kilometers (93-124 miles) in the base of old, thick continents.

Some go even deeper than that, forming at the boundary between the Earth’s mantle and its outer core. These are known as superdeep diamonds.

(For those needing a visual refresher on the layers of the Earth, I found this diagram to be helpful.)

Smith said “very energetic” volcanic eruptions that come from below 200 kilometers bring diamonds to the surface. They are a sort of “accidental passenger” in these explosions.

With them, they carry valuable information in their mineral inclusions, which most commonly include kyanite, garnet and olivine.

Diamond inclusions can help researchers understand the distribution of elements in the Earth’s layers, for example, or when plate tectonics started.

“The diamond is surprisingly good at preserving these materials,” Smith said. “It’s very hard and durable, and good at keeping things from diffusing, or leaking, out of it, and diffusing, or leaking, into it.

“There’s a tremendous of information trapped in these diamonds.”

2. Superdeep diamonds were completely misunderstood until a few years ago.

For many years, diamonds that form at depths greater than 200 kilometers were believed to be small and never gem quality.

But in the past four years, Smith said, researchers have found that many large, high-quality diamonds—Type IIa diamonds (stones with top color and clarity) and Type IIb diamonds, which are gray or blue because of the presence of boron—are actually superdeep stones.

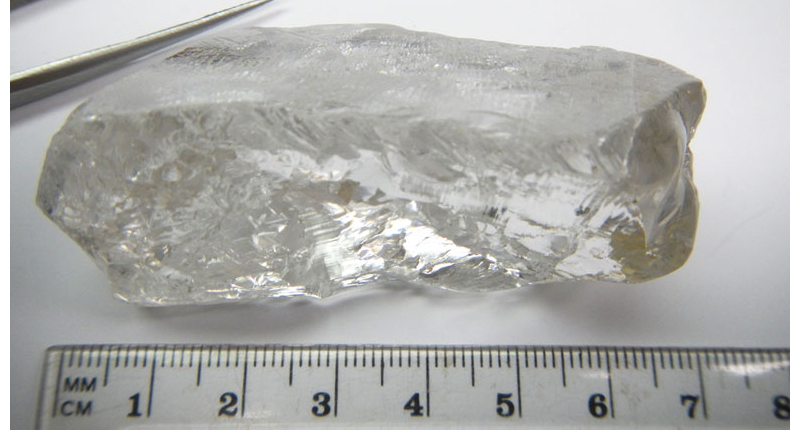

One example of a superdeep diamond is the 404-carat rough diamond recovered from the Lulo Mine in Angola in 2016 (pictured above). Immediately found to be Type IIa and D color, it was the biggest diamond ever known to come from Angola.

The 813-carat Constellation diamond from the Karowe mine in Botswana also is a superdeep diamond, as is the famous Hope diamond and, of course, the largest diamond ever found, the 3,106-carat Cullinan.

Smith said superdeep diamonds are identifiable by the presence of high-pressure mineral inclusions like Ca-pv, calcium perovskite.

3. There are more diamond types than you might think.

Generally, when we talk about diamond types in the trade, we think of Type IIa or Type IIb, terms that speak to a diamond’s physical appearance, its color and clarity and, thereby, its value.

But to geologists like Smith, there are also eclogitic and peridotitic diamonds, two terms I had never heard prior to Thursday’s lecture.

Peridotite and eclogite are two types of rock found in the Earth’s mantle, and diamonds can form in both. These are not superdeep diamonds but the ones found closer, relatively speaking, to the surface of the Earth, also known as lithospheric diamonds.

Peridotite is an igneous rock and is the predominant rock type found in the mantle. If researchers find olivine inclusions in a diamond, then it tells them the host rock was peridotite.

A metamorphic rock, eclogite is much less common. The presence of kyanite inclusions in a diamond indicates it formed in eclogite rock.

4. The oldest diamonds in the world are found in Canada.

Smith’s presentation included a timeline (who doesn’t love a timeline?) that illustrated just how old diamonds are relative to the history of, well, everything.

The Earth dates back 4.5 billion years while the planet’s oldest rocks, found in Northern Quebec, are 4.3 billion years old.

The oldest diamonds follow at 3.5 billion years old and, like the Earth’s oldest rocks, come from Canada, a fact I already was aware of after hearing Karen Smit, another GIA research scientist, speak about the GIA’s Diamond Origin Program back in the fall.

Smit said the oldest diamonds studied by geologists so far have come from the Diavik mine, which Rio Tinto owns and operates in partnership with Dominion Diamond Corp.

To put this in perspective: All these diamonds are older than the Atlantic Ocean, which opened up when supercontinent Pangaea began to break apart about 200 million years ago, and the dinosaurs, which died off 65 million years old.

5. Pliny the Elder had something to say about diamonds.

Smith opened up his talk with a quote from Pliny the Elder, a Roman philosopher and naturalist who lived about 2,000 years ago: “Diamond is the most valuable, not only of the precious stones, but of all things in this world.”

And he concluded it with a quote from himself that I liked: “Every diamond tells a story from a place we can’t go and from a time long since passed.”

I’ve now shared a Pliny the Elder quote; my week is complete.

Have a great weekend everyone, and stay safe.

The Latest

In a 6-3 ruling, the court said the president exceeded his authority when imposing sweeping tariffs under IEEPA.

Smith encourages salespeople to ask customers questions that elicit the release of oxytocin, the brain’s “feel-good” chemical.

JVC also announced the election of five new board members.

Launched in 2023, the program will help the passing of knowledge between generations and alleviate the shortage of bench jewelers.

The brooch, our Piece of the Week, shows the chromatic spectrum through a holographic coating on rock crystal.

Raised in an orphanage, Bailey was 18 when she met her husband, Clyde. They opened their North Carolina jewelry store in 1948.

Material Good is celebrating its 10th anniversary as it opens its new store in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston.

Criminals are using cell jammers to disable alarms, but new technology like JamAlert™ can stop them.

The show will be held March 26-30 at the Miami Beach Convention Center.

The estate of the model, philanthropist, and ex-wife of Johnny Carson has signed statement jewels up for sale at John Moran Auctioneers.

Are arm bands poised to make a comeback? Has red-carpet jewelry become boring? Find out on the second episode of the “My Next Question” podcast.

It will lead distribution in North America for Graziella Braccialini's new gold pieces, which it said are 50 percent lighter.

The organization is seeking a new executive director to lead it into its next phase of strategic growth and industry influence.

The nonprofit will present a live, two-hour introductory course on building confidence when selling colored gemstones.

Western wear continues to trend in the Year of the Fire Horse and along with it, horse and horseshoe motifs in jewelry.

![A peridot [left] and sapphires from Tanzania from Anza Gems, a wholesaler that partners with artisanal mining communities in East Africa Anza gems](https://uploads.nationaljeweler.com/uploads/cdd3962e9427ff45f69b31e06baf830d.jpg)

Although the market is robust, tariffs and precious metal prices are impacting the industry, Stuart Robertson and Brecken Branstrator said.

Rossman, who advised GIA for more than 50 years, is remembered for his passion and dedication to the field of gemology.

Guthrie, the mother of “Today” show host Savannah Guthrie, was abducted just as the Tucson gem shows were starting.

Butterfield Jewelers in Albuquerque, New Mexico, is preparing to close as members of the Butterfield family head into retirement.

Paul Morelli’s “Rosebud” necklace, our Piece of the Week, uses 18-karat rose, green, and white gold to turn the symbol of love into jewelry.

The nonprofit has welcomed four new grantees for 2026.

Parent company Saks Global is also closing nearly all Saks Off 5th locations, a Neiman Marcus store, and 14 personal styling suites.

It is believed the 24-karat heart-shaped enameled pendant was made for an event marking the betrothal of Princess Mary in 1518.

The AGTA Spectrum and Cutting Edge “Buyer’s Choice” award winners were announced at the Spectrum Awards Gala last week.

The “Kering Generation Award x Jewelry” returns for its second year with “Second Chance, First Choice” as its theme.

Sourced by For Future Reference Vintage, the yellow gold ring has a round center stone surrounded by step-cut sapphires.

The clothing and accessories chain announced last month it would be closing all of its stores.