The jewelry collection belonged to “one of society's most glamorous and beautiful women of the mid-20th century,” said the auction house.

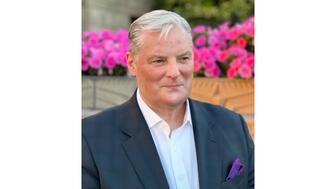

Retailer Hall of Fame 2021: Terry Betteridge

Terry Betteridge descends from a long line of jewelers, but he’s put his own hallmark on the family business.

Greenwich, Conn.—Fate will find you wherever you are.

Terry Betteridge was in the wilderness of British Columbia, Canada, working as a fishing and bow-hunting guide in the summer of 1975, when it came calling.

His father, Bert Betteridge, had suffered a heart attack and needed his son’s help to carry forward the age-old family jewelry business to future glory.

Terry had some big shoes to fill.

Generations of Jewelers

Family-owned jeweler Betteridge can trace its history back to 18th-century Birmingham, England.

At that time, notable silversmith John Betteridge crafted snuff boxes and match holders that were carried in the pockets of well-to-do Englishmen.

In 1892, the Betteridges crossed the pond. Goldsmith A.E. (Albert Edwin) Betteridge Sr. (lovingly known as “the Colonel”) and his wife Lucy were processed through Ellis Island the year it opened, two of millions of immigrants headed to America at that time.

The Colonel would go on to head the International Silver Factory in Meriden, Connecticut, known at the time as “Silver City.”

His son, A.E. Betteridge Jr., opened the first Betteridge jewelry store in the early 20th century in New York City, on Fifth Avenue and 45th Street. Another followed near Wall Street and Broadway in the city’s Financial District.

The family later opened a boutique in the Miami Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables, Florida, a historic locale that has been frequented by stars like Judy Garland and Ginger Rogers, the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, and former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

Betteridge was a celebrated, high-end jeweler of the 1920s and ‘30s, crafting stunning Art Deco designs for the who’s who of the age.

After World War II, A.E. passed the baton to his son Bert, who had served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during the war.

The post-war boom had people moving out to the suburbs in droves and Bert saw an opportunity in tony Greenwich, Connecticut, purchasing W.D. Webb Jewelers and converting it to Betteridge Jewelers.

Bert would run the business for decades, until the summer of 1975, when he suffered that heart attack and made the call to his son, Terry, for help.

By 1978, Terry Betteridge was steering the ship, and he’s remained at the helm ever since.

The Great Unknown

Though Terry descended from a long line of jewelers, he once saw a different path for himself.

“When I was a little kid, I kind of wanted to be a forest ranger,” recalls Terry.

His love of all things wild started young and has stayed with him throughout his life. It makes sense because he’s a little wild himself.

“I’m kind of a risk-taker,” he says. “It could be at a craps table or at a cliff where someone says, ‘I wonder if you can dive off here?’ and I’m gone. I’ve done this all my flipping life.”

Terry channeled his love of nature into a degree in environmental science and considered becoming an environmental lawyer before the jewelry world came calling.

That was maybe for the best, he notes, because his life as a high-end jeweler has allowed him to contribute more to conservation efforts than he would have otherwise been able to do.

He’s donated more than 1,000 acres in the Northeast to a conservation organization. He has 2,000 acres of his own to tend in Vermont as well as around 700 in his home state of Connecticut, and a lumber mill.

Terry finds himself on his land in Connecticut one or two days a week, trimming the fields and building bluebird boxes.

“It does quiet the soul,” he says. “It’s good for you.”

Given his deep love of nature, it seems fitting that Terry would be on board with the growing sustainability efforts in the jewelry world, but it’s not quite that simple.

“It’s the cause of the moment to be sustainable,” he notes, but it, “seems a little artificial and nonsensical. What we do, the way we make our jewelry, we have done the same way for the past couple of hundred years.”

Sustainability is inherent in the existing Betteridge practices, says Terry, like recycling gold.

Terry recalls an anecdote he once heard about American automobile magnate Lee Iacocca visiting a Rolls-Royce factory.

A trailblazer in efficient production, Iacocca asked the president of Rolls-Royce about the last time the assembly line moved. “I believe it moved a week ago last Thursday,” he is said to have retorted.

It’s no different at Betteridge, Terry says, where speed and mass production are not concerns.

“It’s all about the craftsmanship and using these materials we already recycled. Diamonds are recut. Most of the things I get are from an estate,” he says, noting watches are the exception to that rule.

From a dollar-value perspective, a majority of his inventory is estate jewelry, he says.

“I love the old stuff. We’re the ultimate recyclers,” says Terry.

“Each time something is recycled, it picks up a little more history. Recycling infuses the piece with more importance.”

Expanding Horizons

Though Terry may not initially have pictured himself becoming a jeweler, when the opportunity arose, he took it and ran with it.

Under his fourth-generation watch, the family business has grown exponentially, expanding from a single store in Connecticut to affluent towns in Colorado and Florida.

If you can think of a chic American locale, there’s a good chance you’ll find a Betteridge there.

“We look at markets that will give us contact points with exceedingly good customers. These destinations do that,” says Terry.

In 2004, Betteridge acquired jeweler Gotthelf’s in Vail, Colorado, home to the notably fancy Vail Ski Resort. A hub for winter skiing and summer golfing, the small town attracts wealthy visitors year-round.

“I’m kind of a risk-taker. It could be at a craps table or at a cliff where someone says, ‘I wonder if you can dive off here?’ and I’m gone.” — Terry Betteridge

Betteridge met the previous owner, Paul Gotthelf, back in his foot racing days, crashing on Paul’s couch whenever he’d come into town for a race.

He’d also met the store’s employees, who knew and liked him, and he helped out behind the counter now and then, too. When his friend was ready to retire and focus on his mountain biking career, Terry bought the business.

Decked out in dark wood and rich leather, the store’s antler light fixtures are a subtle nod to the rustic mountain surroundings just outside the resort area.

In 2006, Terry got another call from a friend looking to retire and Betteridge made its way to Palm Beach, Florida, acquiring historic jeweler Greenleaf & Crosby.

The previous owner was a friend of Terry’s father, and later of Terry's, when the two shared a hotel room in Basel, Switzerland, during the watch show there.

The store reminded Terry of his own in Greenwich—antique, lovely, and unchanged.

Founded in 1868, the jeweler had been a mainstay on Worth Avenue since the 1920s, as noted by its original Art Deco design.

Its mahogany cases and wall units date back to the days of Standard Oil founder Henry Flagler, whose 75-room, 100,000-square-foot Gilded Age mansion, now a museum, is just minutes away.

Notable for its estate pieces, as well as contemporary designers like Goshwara and Silvia Furmanovich, many of the Palm Beach store’s clientele are collectors with a fine eye.

“Each time something is recycled, it picks up a little more history. Recycling infuses the piece with more importance.” — Terry Betteridge

Terry and the former owner shared a number of customers who summered in Greenwich and wintered in Palm Beach, so it was a good fit.

In 2014, Betteridge arrived in another well-to-do ski town, Aspen.

For Terry, though, there’s more to Aspen than skiing.

“It is a really, real town, not a ski town. It had been a mining town. It has all these historic structures all over the place, sandstone from the 1880s, and stories about various bank robbers escaping from their jails.”

“I got there and discovered the town is really charming. Beautiful.”

Filled with a love for the town, Terry heeded a friend’s suggestion when he said Aspen should be the next spot for Betteridge.

After a few offers, he acquired family-owned Hochfield Jewelers, located inside The Little Nell Hotel at the foot of Aspen Mountain, which he describes as the go-to place for the town’s social events.

After plotting out his expansion, Terry turned his attention back home.

In 2015, the Betteridge flagship store in Connecticut moved down exclusive Greenwich Avenue to a space three times larger.

It features in-store Rolex, Cartier, and Patek Philippe boutiques and a club space, complete with a stocked bar for customers.

The Future of Betteridge

Betteridge is a family business that just keeps on rolling.

Terry’s son Win and daughter Brooke joined their father, marking a fifth generation of fine jewelers.

Win’s wife Natalie caught jewelry fever as well, working in the store and once writing her own jewelry blog. Avid readers visit the store to see her in particular, says Terry.

It’s a feat to be proud of, says fellow fourth-generation jeweler Lee Berg, founder of Lee Michaels Fine Jewelry, a nine-store family-owned chain based in Louisiana.

A friend of Terry’s for more than 40 years, Berg describes him as “fun-loving” and “somebody who runs an outstanding business.”

“In my eyes, Betteridge is an institution within our industry,” he says.

“Terry’s done an outstanding job of taking a family business and continuing to grow it in a fashion that would make the family proud.”

As much as the business has grown, the perks of being family owned is what keeps Betteridge a private company.

Though Terry says he has fielded offers from the likes of Tiffany & Co., there’s a certain freedom in being able to make your own decisions.

Family-run businesses have a strong connection to their surrounding communities and get to be a part of their customers’ lives, an aspect of the job Terry values.

“Betteridge is an institution within our industry. Terry’s done an outstanding job of taking a family business and continuing to grow it in a fashion that would make the family proud.” — Lee Berg, Lee Michaels Fine Jewelry

“You meet people at very good times, when they’re buying for an anniversary or an engagement ring. It’s one of the coolest times in someone’s life, when everything is good, essentially,” he says.

“They’re young and hopeful. They haven’t become old and jaded and shopworn like I have,” he jokes.

Terry’s made a lot of friends over the counter through the years, even meeting his wife that way.

“You become a part of the community in a very real way,” he says.

Decades into his career, as he transitions into, as he puts it, an “old bird,” community outreach has become an increasingly important way for him to give back.

He works with the Greenwich beautification group, a mix of “cool characters,” who plant flowers and back various efforts to keep the town pretty.

“I love that. It gives me a reason to live,” he says.

With hundreds of years of history behind him, Terry foresees Betteridge staying the course in the years ahead, continuing on its jewelry journey—which is catering to sophisticated clientele in lovely locales.

“We don’t seem to have a lot of imagination,” jokes Terry.

The Latest

The update came as Anglo took its third write-down on the diamond miner and marketer, which lost more than $500 million in 2025.

Emmanuel Raheb discusses the rise of “GEO” and the importance of having well-written, quality content on your website.

Every jeweler faces the same challenge: helping customers protect what they love. Here’s the solution designed for today’s jewelry business.

Each received around four years for burglarizing a jewelry store and a coffee shop in Simi Valley, California, last May.

Catherine Aulick, a GIA graduate, received the ninth and final Gianmaria Buccellati Foundation Award for Excellence in Jewelry Design.

We asked a jewelry historian, designer, bridal director, and wedding expert what’s trending in engagement rings. Here’s what they said.

With refreshed branding, a new website, updated courses, and a pathway for growth, DCA is dedicated to supporting retail staff development.

Experts from India weigh in the politics, policies, and market dynamics for diamantaires to monitor in 2026 and beyond.

Beth Gerstein discusses the vibe of the new store, what customers want when fine jewelry shopping today, and the details of “Date Night.”

Are arm bands poised to make a comeback? Has red-carpet jewelry become boring? Find out on the second episode of the “My Next Question” podcast.

The Swiss watchmaker is battling declining sales amid a rapid retail expansion, according to a Financial Times report.

The campaign celebrates Giustina Pavanello Rahaminov, the co-founder’s wife and matriarch of the family-owned brand, for her 88th birthday.

After the Supreme Court struck down the IEEPA tariffs, President Trump imposed a 10 percent tax on almost all imports via a different law.

The vintage signed jewelry retailer chose Miami due to growing client demand in the city and the greater Latin American region.

Former Flight Club executive Jin Lee will bring his experience from the sneaker world to the pre-owned watch marketplace.

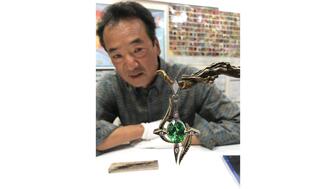

Sakamoto, who died in mid-January following a sudden illness, is remembered for his humility and his masterful, architectural designs.

The April event will feature a new VIP shopping day requiring a special ticket.

Bulgari chose the British-Albanian singer-songwriter for her powerful and enduring voice in contemporary culture, the jeweler said.

In a 6-3 ruling, the court said the president exceeded his authority when imposing sweeping tariffs under IEEPA.

Smith encourages salespeople to ask customers questions that elicit the release of oxytocin, the brain’s “feel-good” chemical.

JVC also announced the election of five new board members.

The brooch, our Piece of the Week, shows the chromatic spectrum through a holographic coating on rock crystal.

Raised in an orphanage, Bailey was 18 when she met her husband, Clyde. They opened their North Carolina jewelry store in 1948.

Material Good is celebrating its 10th anniversary as it opens its new store in the Back Bay neighborhood of Boston.

The show will be held March 26-30 at the Miami Beach Convention Center.

The estate of the model, philanthropist, and ex-wife of Johnny Carson has signed statement jewels up for sale at John Moran Auctioneers.