Associate Editor Natalie Francisco highlights her favorite jewelry moments from the Golden Globes, and they are (mostly) white hot.

5 modern forces that shaped the jewelry industry

In part one of a two-part series, columnist Jan Brassem examines the first two of the five factors he says disrupted and transformed the jewelry industry over the past 35 years.

Since I got my start the gold jewelry industry about 37 years ago, I’ve found myself in the unique position to take a look back--through a rearview mirror, so to speak--to see how our industry has changed over all these years.

After returning from military service and earning a business school degree, I acquired a gold jewelry (mostly rings) manufacturing company. Fortunately for me since I was a novice, the firm employed about 250 experienced managers and skilled craftsmen.

Computers were a novelty then, as they wouldn’t really arrive for another two or three years. We operated manually--no email, no computer-aided work flow nor EDI. Little had changed since the end of World War II, or so it seemed.

We purchased gold castings and genuine stones/diamonds and supplied finishing labor, namely grinding, stone setting and final polishing. Those type of firms were called jewelry contractors in those days.

When all was said and done, we ended with a line of 4,000-plus styles. Using this as a sample line, we took orders from large jewelry retailers, catalog showrooms, wholesalers and other volume users. It was a nicely profitable, price-driven, low-end, word-of-mouth “brand.” To be sure, several competitors used the same operating model.

The firm shipped about 9,000 units a month, few styles costing more than $50. For example, one popular style, targeting teenagers, was a solid, 10-karat gold ring set with a one-point diamond, having a total manufactured cost around $15. We manufactured thousands of these “teen rings,” and our customers sold them for around $30 each. The low-end fine jewelry, sometimes called mass merchandise channel, was robust then.

We, our competitors and many industry leaders, did not foresee the rather unpleasant economic changes that were about to fundamentally and permanently transform the jewelry industry. As William Bridges argues in his bestselling book Managing Transitions (Da Capo Press, 2003), changes that could--and did--wipe out traditional companies only a couple of decades ago are managed more effectively today. More on this later.

Using education, experience and the prism of time, let me briefly summarize five unique industry dynamics (there are more, of course) that, in my view, disrupted and then transformed the U.S. jewelry industry from what it was in my “good old days” to what it is today.

These dynamics--some good, some bad--should give you a pretty good idea of what external forces, timing, management and who

More to the point, however, will your firm skillfully navigate through future unanticipated transitions, or will the changes create the organizational equivalent of a train wreck?

1. The mushrooming gold price

In 1971, President Richard Nixon “closed the gold window” so that foreign governments could no longer redeem their U.S. dollars for gold. From that time on, the price of gold would “float” and be based on the law of supply and demand. By the late 1970s the average price of gold already was around $200 an ounce, up from $44 an ounce in 1972.

As the price of gold quickly rose to $250 an ounce it became a challenge to maintain the important $25 retail price point. When gold reached $300 an ounce it became almost impossible.

In those days, gold represented 20 to 30 percent of an item’s manufactured cost, labor and stones made up the rest. Assuming a retailer’s keystone (100 percent) markup, and their important low-end $25 maximum retail price, it’s no surprise, of course, that the low-end jewelry segment would change when the price of gold started on its inexorable path.

We even looked overseas for merchandise since Asia’s lower labor cost could compensate, or so it was thought, for the higher gold price. That plan was abandoned when gold topped out at $850 an ounce in 1980.

We made the rather unpleasant decision to close our doors when the Reagan-era recession added insult to injury. We were out of life boats.

So retailers went to Plan B, and gradually developed a fondness for silver jewelry with innovative designer styling, consumer acceptance and a “reasonable” cost. Silver jewelry filled the void left by low-end gold jewelry and fit nicely in many showcases.

Over the years, with the price of gold going up and down, the jewelry retailer sagaciously adjusted his product offering and found his footing.

Consumers, in general, now seek fashionable designer brands, particularly in yellow gold.

When all is said and done, the future of the jewelry industry, at least where gold is concerned, is starting to look rosy again, or at least rosier. After years of concern and confusion, happy days could be here. More on this later.

2. Technological un-sophistication

It is unclear to me why the jewelry industry has not kept pace with the technological revolution.

For example, with an abundant amount of tech products and accessories to complement them on the market (tablet computers, laptops, smart phones and watches, etc.), why aren’t some of these also sold in jewelry stores? With the increase of disposable income, jewelry stores seem to be a natural distribution channel, especially to the tech-loving youth market.

I called few technologically advanced friends from Microsoft, Stanford, Harvard and NYU along with a pair of clever marketing geeks from a local high school. I was confident they could shed some light on blending technology with jewelry without altering jewelry’s natural beauty.

After spending a few days thinking about practical technological applications (PTA), the team presented some very preliminary, yet quite innovative, concepts. They’ve found a footing.

-- Micro engineering. It is quite simple to apply micro-engineering principles to jewelry so a pendant, watch, earring, ring, brooch, etc. can change color, look or even character without anything having to come off. A small movement, like watch movements, are virtually invisible and are simple to use. Without getting too technical here, all that is needed is a strategically placed mechanical bearing so a watch, for example, can have a watch face on one side and a lapis stone on the back side. Additional costs are negligible. The Eclipse brand successfully pioneered this concept in silver.

-- iPod technology. iPod technology is becoming smaller and smaller. The largest part of an iPod Nano is, of course, the case. The team estimates that a medium-sized pendant, particularly a locket, could be designed so an iPod Nano can fit inside the locket. The locket’s chain will act as the wire with subtle extensions for ear plugs.

-- GPS/camera tracking. It is only a matter of time before GPS miniaturization will allow expensive jewelry, especially pieces with laser-engraved diamonds, to be tracked. The small GPS systems are not on the market yet, but the team estimates they will be in a year or so.

-- PTA miniature applications that haven’t been developed yet. The team reported that cameras, speakers, recorders and the like could be integrated into jewelry; if not now, then in the near future. The jewelry designer can simply work with technology-trained innovators to create techno-pioneering designs.

A good example is Galatea, which has developed the Momento pearl jewelry brand that contains an embedded chip that uses near field communication (NFC) technology. The wearer can record messages that later can be played on mobile devices.

All of these technological developments need an important ingredient for stardom, says Harvard’s Jim Gilliam, namely a loud voice and a kumbaya product.

I don’t necessarily agree. Truth be told, of course, any pioneering product usually needs a persuasive “rainmaker,” a company who bangs their drum the loudest. But it’s clear to me when it comes to risk- taking, innovation always trump noise.

Did I hear that Apple Inc. is quietly looking for salesmen to sell their smartwatch to jewelry stores? A perfect example of innovation over noise.

Please stay tuned for my three remaining factors.

The Latest

Yantzer is remembered for the profound influence he had on diamond cut grading as well as his contagious smile and quick wit.

The store closures are part of the retailer’s “Bold New Chapter” turnaround plan.

Criminals are using cell jammers to disable alarms, but new technology like JamAlert™ can stop them.

Through EventGuard, the company will offer event liability and cancellation insurance, including wedding coverage.

Chris Blakeslee has experience at Athleta and Alo Yoga. Kendra Scott will remain on board as executive chair and chief visionary officer.

The credit card companies’ surveys examined where consumers shopped, what they bought, and what they valued this holiday season.

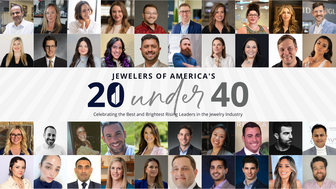

How Jewelers of America’s 20 Under 40 are leading to ensure a brighter future for the jewelry industry.

Kimberly Miller has been promoted to the role.

The “Serenity” charm set with 13 opals is a modern amulet offering protection, guidance, and intention, the brand said.

“Bridgerton” actresses Hannah Dodd and Claudia Jessie star in the brand’s “Rules to Love By” campaign.

Founded by jeweler and sculptor Ana Khouri, the brand is “expanding the boundaries of what high jewelry can be.”

The jewelry manufacturer and supplier is going with a fiery shade it says symbolizes power and transformation.

The singer-songwriter will make her debut as the French luxury brand’s new ambassador in a campaign for its “Coco Crush” jewelry line.

The nonprofit’s new president and CEO, Annie Doresca, also began her role this month.

As the shopping mall model evolves and online retail grows, Smith shares his predictions for the future of physical stores.

The trade show is slated for Jan. 31-Feb. 2 at The Lighthouse in New York City's Chelsea neighborhood.

January’s birthstone comes in a rainbow of colors, from the traditional red to orange, purple, and green.

The annual report highlights how it supported communities in areas where natural diamonds are mined, crafted, and sold.

Footage of a fight breaking out in the NYC Diamond District was viewed millions of times on Instagram and Facebook.

The supplier has a curated list of must-have tools for jewelers doing in-house custom work this year.

The Signet Jewelers-owned store, which turned 100 last year, calls its new concept stores “The Edit.”

Linda Coutu is rejoining the precious metals provider as its director of sales.

The governing board welcomed two new members, Claire Scragg and Susan Eisen.

Sparkle with festive diamond jewelry as we celebrate the beginning of 2026.

The master jeweler, Olympian, former senator, and Korean War veteran founded the brand Nighthorse Jewelry.

In its annual report, Pinterest noted an increase in searches for brooches, heirloom jewelry, and ‘80s luxury.